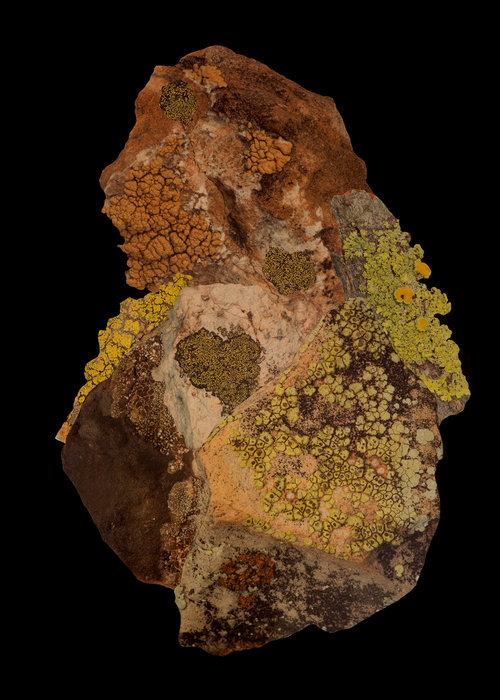

Foliose Fruticose Reconsiliation, 2018

Lessons From Other Life Around Us

Sarah Hearn works at the intersection of science and science-fiction by studying environmental creatures and phenomena. In this interview, Hearn discusses her process and inspiration for works that involve the largess of the sky to the tiniest most incredible beings.

Interview conducted by Olivia Ann Carye Hallstein

You describe your work as hovering between “studies of life on planet earth” and in a “hazy atmosphere of science fiction.” Where do you experience the break between the two?

I believe this boundary between factual understanding of science and visionary predictions of science fiction sometimes collide and the various breaks between these two worlds are constantly shifting. Our understanding about the universe around is forever bombarded with new knowledge. At times, these moments force us to shed previously held beliefs sometimes about the core of our beings, or types of matter lurking in our universe. These uncomfortable places of limited human knowledge are infinitely interesting.

Although I have several projects that are science fiction in nature, Symbiotic Cooperation, the Lichen Field Guide and and the Lichen Study Guide collaborations are examples of projects with the goal of scientific accuracy. I enjoy working in a variety of ways, so being able to tax both sides of my brain keeps things interesting. Having a range of projects in my practice feeds a strange creative/detail obsessed cycle.

I believe if we can be open to other kinds of intelligence, we could learn lessons from other life around us, about how to better adapt- even during something as extreme as climate collapse. These types of studies sound worth our time.

Parmotrema hypotropum, Urban Colonization, Colony 11, 15" x 28" hand-cut vinyl photographs for site-specific installation at Anita B. Gorman Conservation Discover Center, Summer 2015

Have there been discoveries you have made that have seemed like science fiction, but were real to earth (ex. Your work with Lichens)?

Yes, all the time. It’s true that the more you know, the more you realize how limited your knowledge is—you know? But in general, I am so amazed by how weird tiny things are. I get excited thinking about the measurable electric current that pulses through all living things, and by the ability of microbes to survive a 120 million year deep freeze and come back to life in a lab over a few weeks (proof zombies are real). Lichens are excellent examples of alien-like terrestrial life. They cover an estimated 8% of the planet with an estimated 4,000-6,000 species in North America alone. We still have so much to learn from them. Lichen even survived space travel and intense exposure to the atmosphere. I have been working with them closely for 9 years now and I still learn new things from them all the time. They marvelously demonstrate how tiny life forms contain multitudes of power and different kinds of intelligence. The recent project, Astrobiological Futures has me thinking about potential space life forms and lichen like organisms don’t seem that far-fetched.

Staying connected to my natural environment is crucial for my creative and spiritual wellbeing. This work promotes learning to see beyond the human limits and reconstructing our ways of living with nature. When we feel more connected to our living environment, we tend to take better care of it. I guess you could classify it as microactivism? Tiny changes with big impact.

Cumulus and Stratocumulus, 2016

What revelations did you have about the stratosphere while looking at so many images of clouds?

I grew up landlocked in Oklahoma—a place where homes and towns are frequently wrecked by the fickle mood of the weather. I remember learning how to tell a wall cloud from other cloud types at an early age. Ultimately this project grew out of a desire to know more about all the other clouds that appear and disappear so quickly above us. The world is constantly changing and observing clouds is a wonderful immediate reminder of this. Mamatus clouds are universally fascinating.

In “Above” you use frescos to present images of cloud types on their international weather systems symbols. Can you explain the choice of using frescos (an earth medium) to present the atmospheres and clouds?

The choice to transfer the images into fresco slurry was very intentional. I have roots in traditional photography and love darkroom printing. Making the switch to digital printing didn’t fill my personal need for a tactile, messy process. I had been using the symbols to code the project, but the work needed to exist beyond square or rectangular frame boundaries- suddenly I knew the symbol shapes were the solution. I developed the installation idea to hang them at different heights depending on where the clouds would occur in the atmosphere, ultimately these organic configurations feel like a weather system passing through a gallery space. Because I am using a fresco transfer process, no two are the same—a perfect analogy for clouds. For the frescos to set, I am dependent on the weather, I can only make them on drier days with mild temperature and low humidity. I love this need for cooperation to make this work- a beautiful reminder of our small place within an expansive universe.

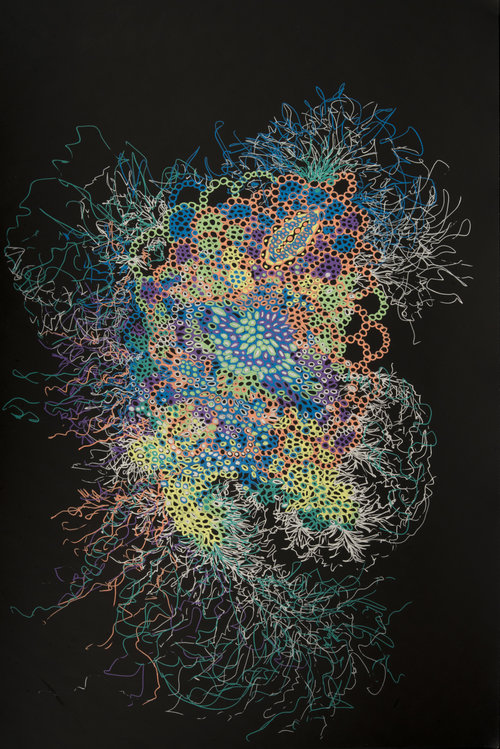

Untitled drawing #6, 2016

Can you describe your process when creating an artwork? Do you collect things out of initial interest and then wait for inspiration through research or do you gather materials with a project in mind?

Well, there isn’t a single answer for this- ideas for projects come in different ways. I think of my art practice as a living breathing thing that changes, expands and contracts. I think I am always in conversation with the work I am researching and making; I am also receptive to new ideas as they come, but recognize they sometimes take years to come to fruition. So working with lichen came about from discovering it along the coast while working on another project focused entirely on ocean life. That was in 2009. It took me three full years before I began focusing on it and truly working with it. The first project working with it- the lichen was the conceptual framework- I set out to behave symbiotically, like lichen. I asked the public to mail small samples of lichen to me. I photographed them, identified and cataloged them and donated them to a university herbarium. Each person who contributed lichen (or at least what they thought was lichen) received a small work of art, public recognition for their contribution and regular project updates on the project. Sometimes I set up the art making practices as a formula with strict rules—this was the case for an Unnatural History. The drawings where a strict size, all were printed in the color darkroom, each was mounted to a 8” x 8” plate and all were presented with their elemental symbol and atomic number. Many creatures in the catalog were real, and many were fictional, but the set of rules, leveled the viewing field and viewers start to make assumptions about the veracity of information in front of them. Other times, I just make art—I don’t think, I just let myself be creative and respond to the things I am currently thinking about.

Many of your works use bright colors on dark or black backgrounds. Can you talk about this choice and its relationship to both color theory and the scientific process?

The color choices are definitely influenced by my roots in the color darkroom. For years I was drawing negatives and printing them- so the drawings were always the color reverse of what I wanted the prints to be and because they are photograms—they float in a dark background. It seems as I’ve continued to make new work, much of this same color palate and aesthetic prevails. As for the choices for black backgrounds, and stark white backgrounds: yes, they are visually connected to darkroom photograms, but this choice also mimics formal scientific illustration where the subject presented by the artist is often isolated from its surroundings.

Artificial Colony #11, 2015

For many, including myself, the pandemic has brought us to spend more time in natural environments. How do you feel like the lock-down situations has affected your practice and goals as an artist?

Well, like many, my life has changed dramatically during the pandemic. I wish I could say the first 6 months were positive, but I was living in some kind of hyper-excited-over-tired state working full time (not from home!), managing a four-year-old whose child care went “online” and trying to stay on top of my art practice. Needless to say, it wasn’t sustainable. Spending time in nature, cooking and baking have gotten me through the difficult days, weeks, and months. In September, I made the decision to step down from my full-time position as an arts administrator and focus on my personal art career and my family. My goals for my art practice have come into full focus again and it’s feeling wonderful to give the work the time and space it needs grow. As someone who has juggled a little too much for far too long, I am so thankful for this transition.

Sarah Hearn is an interdisciplinary visual artist and citizen researcher. Through explorations of biological life and natural phenomena, her work inhabits two realm; one grounded in studies of life on planet earth, and another hovering in a hazy atmosphere of science fiction. Hearn's work was presented in the 2018 exhibition, Big Botany: Conversations with the Plant World at the Spencer Museum of Art in Lawrence, Kansas. Recent solo exhibitions include: Microtopia and Accumulation at Leedy-Voulkos Art Center in Kansas City; An Unnatural History at Art Center of the Ozarks in Springdale, AR; and Invisible Landscapes at University of Notre Dame. Hearn earned a BFA from the College of Santa Fe, and an MFA from Rochester Institute of Technology.