In a time of pandemic crisis, how do we re-value what care means for all living beings?

There is a species of moss growing on the outside of my bedroom windowsill that I hadn’t noticed until recently. Two clumps of bryophyllum hiding in the shadow of a ventilation duct that extends to the roof of my apartment building in Prospect Heights, Brooklyn. Known for their love of cool, moist and dark spaces, moss or byrophyte is a phylum of three kinds of non-vascular plants that use rhizoids instead of roots and reproduce using spores. Although an uncommon site in some parts of New York, my windowsill is apparently a desirable habitat and has offered unlikely solace during an increasingly precarious time.

As a member of the Environmental Performance Agency, an artist collective founded in response to the dismantling of the US Environmental Protection Agency, I have been thinking a lot about the view from my window as of late. From my bedroom, I can see a rapidly expanding border of knotweed encircling a now desolate restaurant patio, a Siberian elm making use of an underused backlot, and a weedy patch of shepherd's purse, plantain, dandelion and horseweed. These marginal spaces offer a habitat for insects, squirrels, birds and other organisms, and more recently has become my only view of urban “nature” or multispecies life.

In New York, we’ve been on PAUSE since March 22, 2020, a collection of social distancing policies that have prompted those with the privilege to do so, to work from home while “essential and frontline workers” continue to keep the City in a reduced state of operation. The impacts of Covid-19 have been uneven to say the least, with communities of color and low income residents hit hardest in terms of confirmed cases but also a range of social and economic impacts. Cities like New York are now the “vanguard” on the pandemic front, making visible the complexities of urban density, as well as decades of disinvestment in health care, education and affordable housing among other issues.

As both a response to our current moment and continuation of the EPA’s past work, we launched a new effort called the Multispecies Care Survey on Earth Day 2020. The project is a public engagement and data gathering initiative that aims to provoke new forms of environmental agency to de-center human supremacy and cultivate the co-generation of embodied, localized plant-human care practices. What do we mean by plant-human care practices? Methods for attuning oneself to a vegetal perspective - moving, breathing, listening, and working with spontaneous urban plants and other organisms as guides, collaborators, and mentors. Invitations for developing new forms of environmentalism and stewardship that decenter the human and honor the agency and possibility of multispecies communities. Spaces to reimagine and embody what care means in a time of global crisis.

Originally conceived of as a public artwork launching at the Old Stone House that would travel to communities throughout NYC, the project was re-designed as a digital platform integrating a need for social distancing. Although hesitant to move our embodied and physical practice of being together with the city’s weedy and spontaneous urban plant communities, the EPA collective felt a need to reframe our practice to reflect our current context, and to collect data on how communities across the city and US are adapting, coping and developing new strategies for resilience and connection.

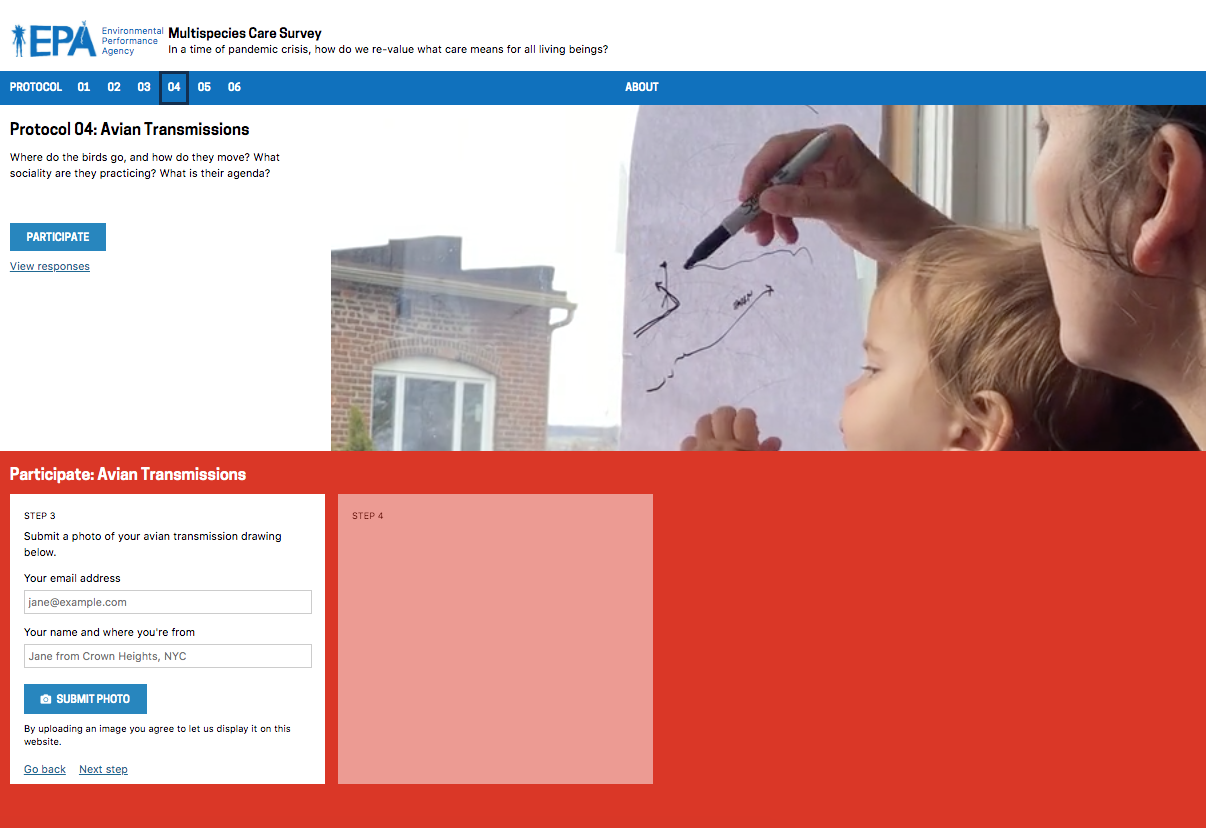

The Survey website currently includes 6 “protocols” or prompts for noticing and engaging with multispecies communities through a window, balcony, backyard, or stoop. “Protocol 01: Temperature Check” for instance invites participants to consider which window you look out of more often since the crisis, to move towards this window and place an area of your body against the window pane to consider how it feels. What temperature does the glass offer? What temperature does the sunlight offer? How do you feel the climate’s temperature? After a brief engagement, the participant is then prompted to submit a photograph and brief audio recording to describe the experience, and what the view they encountered. In Protocol 04: Avian Transmissions, participants are invited to notice birds as they pass by one’s window by first observing and then placing a piece of paper to the window and create marks that follow the bird’s flight/position. A quick documentation creates an archived record of the experience. We use the term “survey” broadly, drawing from a history of public land surveys that have defined our artificial borders and notions of land use, and also survey practices that range from national undertakings like the US Census to regional biodiversity counts to collect large datasets.

Each protocol is also linked to a specific call to action related to recent changes and rollbacks to environmental policy occurring at the US EPA, or other federal and state agencies. An email notification reminds the participant to learn more about each issue and to further act by signing a petition, calling their congressional leader, or getting involved in a local movement or direct action. In “Protocol 05: Essential Tree Labor”, which prompts participants to notice and care for a street tree, we call attention to the rollback of the Clean Power Plan. This Obama-era policy required utilities to reduce carbon dioxide emissions from existing power plants by 32 percent from 2005 levels by 2030. The rule was replaced in 2019 with the “Affordable Clean Energy” (ACE) rule which weakens emissions standards. Through the survey, we ask: “What kind of energy policy would street trees endorse?”

Over the past 4 years, the U.S. EPA and other federal agencies have rolled back over 95 rules put in place to protect environmental health, supporting the interests of the coal, gas, and oil industries, along with Big Agriculture. The Multispecies Care Survey continues our work to bring awareness to these increasingly alarming rollbacks under the 2016-2020 presidential administration. Even in this time of global crisis, the US EPA continues its assault on environmental policy and health protections for communities across the country. In late March, the US EPA announced new “guidelines” for how companies monitor environmental violations, pollution and hazardous waste waiving a requirement for reporting, and will not issue fines for violations. Former EPA Administrator, Gina McCarthy, called it “an open license to pollute.” On March 27, 2020, the US EPA announced changes to how gasoline will be mixed in the face of potential shortages, which will likely result in more air pollution nationally. Just last month in April 2020, the US EPA extended public comments on the rollback of regulations for safe methods of coal ash disposal, the byproduct of dirty coal power plants. Power companies and private interests dump this waste into unlined ponds, which contain deadly poisons and radioactive substances, including carcinogens like arsenic, and neurotoxins such as lead and mercury, threatening drinking water nationwide. And on April 16, 2020, the US EPA weakened regulations on the release of mercury and other toxic substances from power plants and other industries, which the New York Times and environmental groups point out would effectively loosen the rules on other toxic pollutants.

This is all happening at a time when we are dealing with a collective global trauma unlike many have seen in their lifetimes. And alongside an ongoing effort to censor scientists and undermine what little confidence the US had left in scientific research for the public good. (See the so-called “Strengthening Transparency in Regulatory Science” which public health advocates and environmentalists have dubbed the “Censored Science Rule”.)

Since launching the project we’ve received dozens of responses from communities across the US, offering a glimpse into the multispecies worlds on view from one’s window. We are hoping to deepen engagement with the Survey through virtual Care Circles starting on May 9th, bringing together participants to share their experience of engaging with a particular protocol and to think through what new forms of embodied environmental action we can collectively envision. As a long-term and ongoing effort, we intend to maintain the Multispecies Care Survey through the US Elections in early November. The data collected -- images, audio recordings, videos, embodied experiences -- will ultimately be used to draft a new piece of policy we’re calling “The Multispecies Act.” This Act aims to offer a set of embodied, actionable principles for centering spontaneous urban plant life as one means (among many) of contending with the failure of our environmental regulatory apparatus to deliver policy that protects and values life both human and non-human.

As I write, this is day 56 of quarantine in my own apartment. Although I only have a few windows overlooking a patchwork of under-used lots and backyards, the emergence of Spring and the Survey’s protocols have brought new discoveries of life along the margins. And perhaps offer a set of novel interactions and embodied practices that help me cope through uncertain times. Now when I look out my window, I see things a bit differently and my powers of attunement sharpened. The simple practice of embodied observation offering some inspiration for how to persist in a time of global crisis and collective reimagining.

Submitted by Christopher Kennedy, assistant director at the Urban Systems Lab (The New School) and lecturer in the Parsons School of Design.