An Interview with Sarah Kanouse

By Olivia Ann Carye Hallstein

My practice is totally affected by being quarantined. I'm working on the dining room table on a failing laptop that I couldn’t get fixed before all of the computer repair places shut down as nonessential businesses. sk

Sarah Kanouse was preparing to tour her original work My Electric Genealogy throughout Southern California when the Covid-19 pandemic broke out. She helplessly watched as five years of work and preparation was put on hold. The work explores the social justice impacts of her family inheritance and intergenerational environmental responsibility.

OH: I understand you’ve had to make some difficult decisions as a result of the pandemic, including leaving your residency locality in Munchen.

SK: Yes, I had to leave Germany abruptly last week for fear of getting stuck there for another six months, well beyond my housing contract and income. I’ve been under house quarantine in Boston for 8 days, so it’s mostly been my community here supporting me. I’ve figured out how to make some masks and plan to help deliver meals when I get out of quarantine next week.

OH: What response have you had to the ecological changes resulting from the global quarantines and how has this affected your practice?

SK: We’re getting a crash course in degrowth--the radical contraction of our economies that is needed to mitigate climate change, but that would have to be carefully planned not to make far, far worse the violent inequities of contemporary capitalism. I hope that the mutual aid networks we’ve seen spring up in neighborhoods everywhere and the ways that once-radical ideas like UBI and free health care suddenly seem eminently sensible is a preview of a beautiful eco-social future. But, unfortunately, the right-wing governments are using the shock of the pandemic to further gut environmental regulations, trample privacy, and curtail dissent. Keystone XL just a fresh infusion of money and is full speed ahead, and it barely registered in the news.

OH: You describe that the show “My Electric Genealogy” traces your relationship to the environmental and social justice impacts of (your) family inheritance.

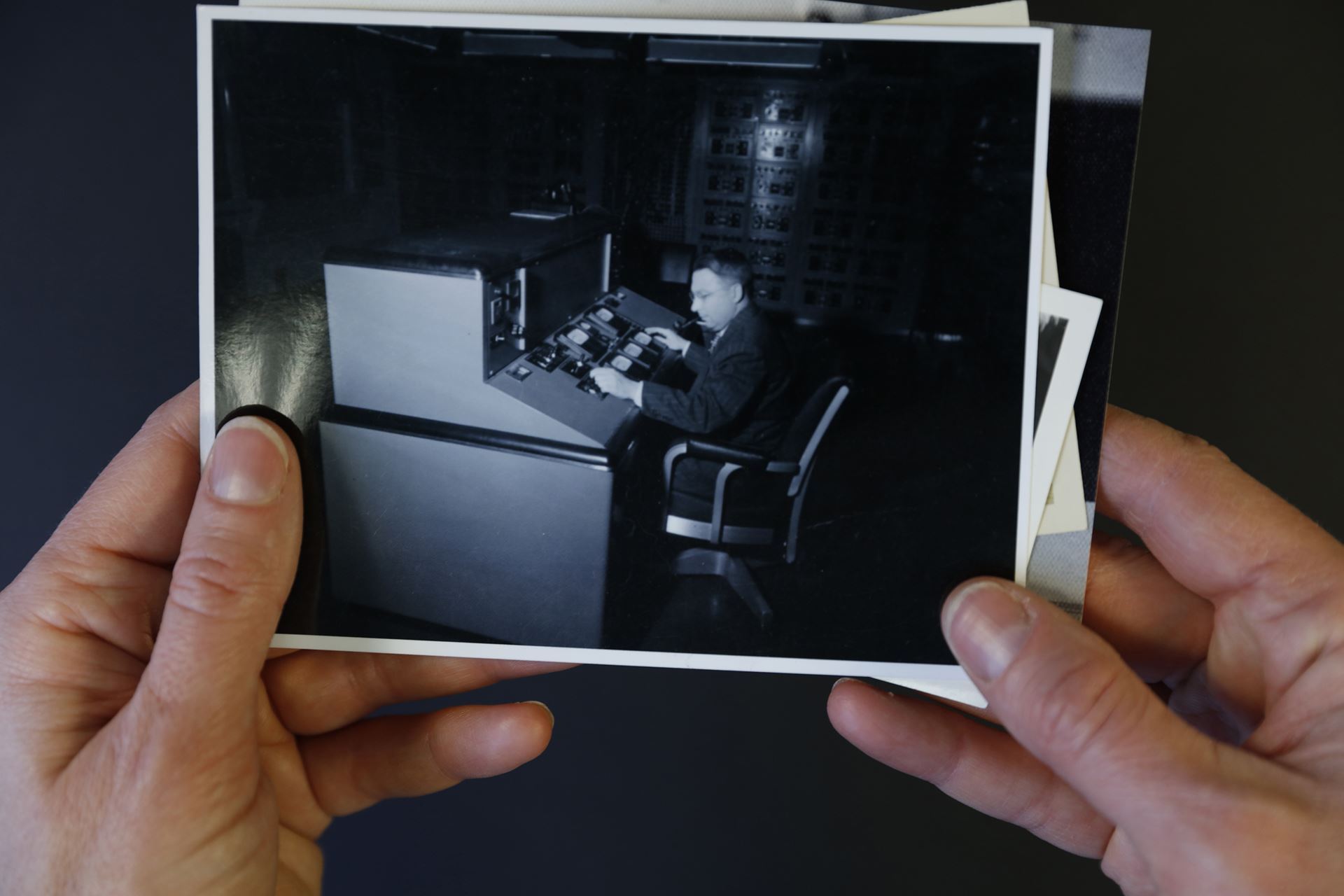

SK: Well, my grandfather worked for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power from the 1930s to the 1970s—a 40-year period in which the city’s population more than doubled and the Great Acceleration of energy consumption really took off. His entire career was devoted to ensuring that the city had enough power to support rapid population growth that was concentrated in hot, arid places that required ever-increasing amounts of energy to make comfortable according to white, middle class standards.”

OH: What are some of these environmental and social justice impacts?

SK: Several power plants were built in this era in the Four Corners area hundreds of miles away either on or encircling the Navajo and Hopi reservations. Indigenous people and the animals and plants they mutually depend on experienced all the adverse health and environmental impacts of these plants and their associated coal mines but did not benefit from any of the electricity.

OH: Can you please share a specific story from the show?

SK: In the performance, I contrast this story with my grandfather’s plan to build a nuclear power plant in Malibu. This privileged beachfront community was able to successfully mobilize to defeat the DWP’s planned Corral Canyon Nuclear Power Plant, which my grandfather envisioned as the first in string of 30 nuclear power plants along the California coast. In addition to the environmental injustices involved in electrical generation in the twentieth century, the transmission infrastructure both reflects and contributes to economic and racial segregation in the built environment in the present.

OH: In the description of the solo show “Electric Genealogy” you question what role you and your identity play in the destructive infrastructures that are involved in colonization and industrialization. Tell me more.

SK: I’m strongly influenced by the environmental philosopher Kyle Powys Wyte (Potawatomi) who has called on white environmentalists to take responsibility for the ways that their (which is to say my) environmental consciousness has been shaped by white, settler colonial values and how “we” benefited intergenerationally from the very planet-imperiling practices that we now decry.

OH: For those of us who may not get the chance to see your show, have you come to any personal conclusions on the topic?

SK: The project is very personal. My grandfather was a complicated and difficult man—scornful of the burgeoning environmental movement; critical of the educated wife who gave up her own career to support his; politically conservative and deeply religious; harsh and even violent with his children. But he is also part of me. As an artist, I identify with his ambition and almost megalomaniacal focus on his life’s work. He loved photography and took hundreds of images of electrical transmission and generation systems. But what do we do about ancestors whose actions were the ones being rightfully resisted? I think of the project as a reparative project—critical of my grandfather’s legacy, of course, but also one that tries to build something out of the fragments, ruins, and traces that he and his generation left.

OH: Is the mid-century men’s suit that you wear during the performance meant to emphasize this?

SK: Wearing a suit that could have been my grandfather’s and adding and subtracting different costume elements over the course of the performance is one of the ways that I work through my connection to him and his time. It’s also a way of playing with and multiplying the possibilities for gender expression to resist the normative hetero-patriarchy which much of US infrastructure assumed: private, domestic, feminized spaces of consumption and rugged, masculine, high-tech spaces of production.

I hope that the performance prompts the audience to consider their own co-subjectivity with modern infrastructures, since we are at a moment in which they must fundamentally be reworked and rethought. sk

OH: You embody multiple generations in the show in order to ask what intergenerational environmental responsibility might look like. How might it look in your perspective?

SK: Because the environmentally unjust present was not merely what Whyte calls the environmental fantasies of my ancestors but also my grandfather’s actual life’s work that is actively imperiling the future that my child will inhabit. The performance is in some ways a counterfactual dialogue with the political and cultural legacies of my grandfather's life's work—one that's needed if we are to work through the legacies of modernism, technocracy, and growth-at-all-costs that continue to animate green capitalist approaches to climate adaptation.

OH: Much of your early work was in film. When did you decide to work in live performance? How has the medium informed the process?

SK: I started this project thinking I was making a film. Like I often do, I wrote a lot, shot a lot of material, and did some talks, which steadily became more and more performative. At one point, the script was 80 pages (a lot to memorize!), and I had done absolutely no acting since junior high. So, it slowed the creative process down immeasurably, but also in really exciting and fun ways. I audited a university acting class, joined a contact improv circle, consulted with performance artists as I reworked and finished the script, and worked with a choreographer friend to think about how my movements can convey the idea of being embodied by and related to something as big and diffuse as the electrical grid. It took me awhile, but the project couldn’t go back to being a film—it’s just too much of hybrid creature—movement, sound, storytelling, projected moving images, sculptural set design, videoclips—to flatten on a screen.

OH: What are your next steps?

SK: Good question - and I wish I had an answer! I was just starting to set up dates for fall on the east coast, where I’m based, when the pandemic began heating up. Those were all in the early stages and are just impacted by the pandemic as the postponed spring shows, since the canceled/postponed events of the spring should be rescheduled if at all possible. It also feels incredibly icky to be worrying about the impact on this project when people are sick and dying or losing their jobs.

So, I’m taking this moment to take stock not just about this project but how I live—the ways that my creative ambitions unwittingly replicate some of my grandfather’s worldview, for example—and knowing that there cannot be business as usual after this.

Olivia Ann Carye Hallstein is a Cambridge, MA based artist/writer and ecoartspace member.