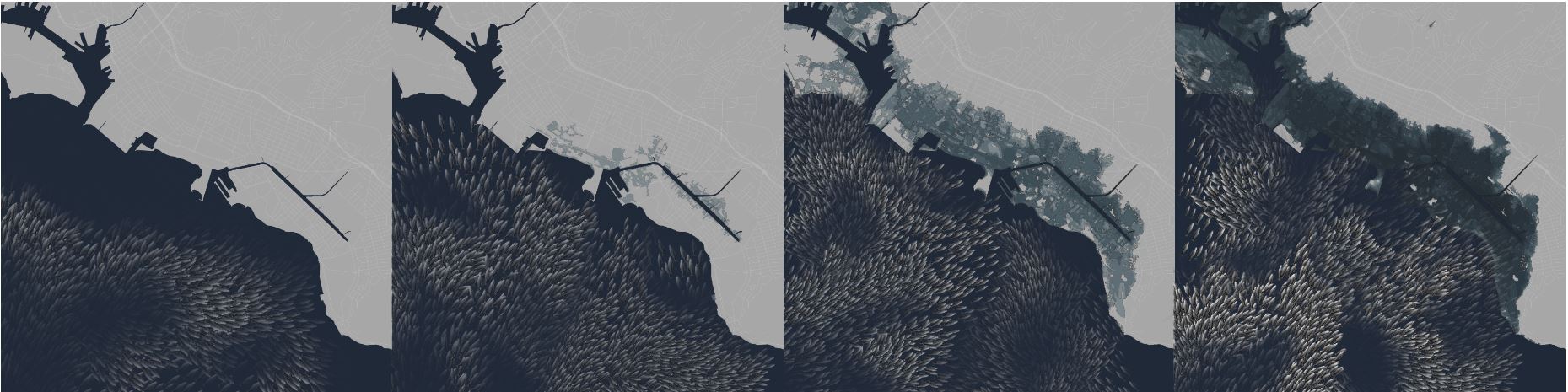

Front: Charles Lim, SEA STATE 9: proclamation, 4K video, 2017, SEA STATE 9: proclamation: the sandpapers, bookshelf and books, 2017 and SEA STATE 9: proclamation: sand graph, photographs, 2017; and Back: James Jack, SEA BIRTH THREE, 4 K digital video, 2020, SPIRITS OF ŌURA, handmade walnut ink on paper, 53 “ X 174.4 “ 2020, and HOME FOR PĪDAMA, aged driftwood, 29.5 “ x 13” x 8,”2020; Photo Credit Kelly Ciurej

For Pacific Islanders, sea level rise is an existential threat. Island communities in the Asia Pacific are seeing their traditional ways of life threatened and many are experiencing coastal erosion, diminishing fresh water tables and dramatically stronger storms. For example, the Marshall Islands, which lie only six feet above sea level, experiences tidal flooding once every month. According to Marshall Island Foreign Minister Tony de Brum, the island of his childhood is “not only getting narrower – it is getting shorter…There are coffins and dead people being washed from graves – it’s that serious.”

Inundation: Art and Climate Change in the Pacific currently on view at the University of Hawai’i Manoa, includes nine Pacific artists who address the impacts of rising of sea levels resulting from climate change, and the flood of emotions that the inundation unleashes. Curated by Jaimey Hamilton Faris, Associate Professor of Art History and Critical Theory at the University, the exhibition features works that convey the aesthetics of water and the vulnerability of Asia Pacific Island communities in Hawai’i, the Kingdom of Tonga, the Philippines, Okinawa, the Republic of the Marshall Islands, Tuvalu and Singapore both visually and through the spoken word. Artists included in the exhibition are: Hawai’i-based fiber and installation/performance artist, Mary Babcock; Kanaka Maoli sculptor and installation artist, Kaili Chun; Philippine artists and siblings, Martha and Jake Atienza, who work under the platform DAKOgamay; socially engaged Singapore artist, James Jack; Marshallese poet and performance artist, Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner; artist and scholar of Native Hawaiian, African-American, Japanese, Caddo Indian and Punjabi descent, Joy Lehuanani Enomoto; Singapore performance artist, photographer and videographer, Charles Lim Yi Yong; and New Zealand-born artist of Samoan and Australian heritage, Angela Tiatia.

In a recent conversation with Faris, she explained that her goal was to create an exhibition on the climate crisis that did not follow the usual formula for addressing well-known scientific and technological factors but was primarily seen through the lenses of climate justice and culture. She also wanted to “bring regional artists from large coastal island cities together with artists from small islands so that they could dialogue with each other about the shared challenges they face as a result of the climate crisis and potential alternative solutions for their homelands.”

All of the artists in Inundation promote the inclusion of Indigenous voices and environmental knowledge in the discussion of the current climate crisis in the Pacific islands. Rejecting traditional governmental solutions to flooding based on colonial history, including coastal defense systems and land reclamation projects, they imagine alternate ways of remediating the environment.

In her work, entitled Hū mai, Ala Mai, for example, Kaili Chun has created maps displaying the past and projected future shorelines along Waikiki, the Honolulu airport and the Marine Corps Base Hawai’i in O’ahu. Indicating where inundation will most likely occur and how it’s connected to the history of land appropriation and reclamation during colonization and development, the maps are overlaid with native varieties of fish that once swam in the estuary streams. Hū mai, Ala Mai imagines how a reconnected watershed can be restored into an abundant tidal ecosystem by letting the rising waters back into the places they had previously been. Her work also emphasizes the native Hawaiian values of “abundance, care and respect for the moving waters.”

Left: Kathy Jetnil-Kijiner and Joy Lehuanani Enomoto, Sounding, installation with baskets, sounding line, drawing and sound recording, 2020 ; Mary Babcock, Lotic Sea, (Center), stitched wax paper and sea salt, 2020; and Right: Kaili Chun, Hū mai, Ala mai, Ink-jet digital collage on archival paper, 24”X 96”, 2020 Installation View. Photo Credit: Chris Rohrer

In a complex installation entitled Sounding, by Kathy Jetn̄il-Kijiner and Joy Lehuanani Enomoto, the artists employ the patterning, intersections and strands of weaving, with the sounds of water to suggest how all Pacific island voices, including women and Indigenous ones and all strands of knowledge, including ancestral, should be part of the planned solutions to the climate crisis.

A poem by Jetn̄il-Kijiner in the exhibition catalogue reminds us of what happens when “strands” are left out of the conversation:

Look – I missed a strand.

I missed a strand, and now could we be unraveling?

Has the day come when we can talk? Maybe the day has come when we must talk. Because something is eating islands. There are islands dying. There are voices telling us to destroy thousand year old limbs like it’s nothing.

Like it’s not another strand unraveling. Like it’s not another woman sinking to the bottom. Sinking boulders tied to feet, body caged in a woven tomb.

We missed a strand and we named her monster.

Accompanying the exhibition is a comprehensive catalogue and a full range of community events, including HIGHWATERLINE: HONOLULU, which invites community participants to visualize how rising tides will impact Honolulu by walking through the Kaka’ako area. Organized by Christina Gerhardt, Associate Professor at the University of Hawai’i Manoa, this activity is a recreation of artist Eve Mosher’s original 2007 HighWaterLine community art project that marked over 70 miles in the New York City boroughs at risk for major flooding from rising tides. The Guide to Creative Community Engagement was written by Eve Mosher and Heidi Quante, and provides a roadmap on how to realize a HighWaterLine locally.

Inundation: Art and Climate Change in the Pacific is on view through February 28, 2020 at the University of Hawaii Manoa. The exhibition will travel to the Donkey Hill Art Center in Holualoa, on view March 28 – June 26, 2020.

Mention: ecoartspace founder and curator, Patricia Lea Watts, coined the phrase “replicable social practice” in 2012 and was the lead writer for the original HighWaterLine ACTION GUIDE, co-written with Eve Mosher, offering a range of strategies for making a high water demarcation. Funded by The Compton Foundation, San Francisco.

Susan Hoffman Fishman is a painter, public artist and writer. Since 2011, her paintings and installations have focused on water and climate change. She is the co-creator of a national, interactive public art project, The Wave, which addresses our mutual need for and interdependence on water. As one of the core writers for the international blog, Artists and Climate Change, her series “Imagining Water” is published monthly.