Aerial image of land containing mineral assets

Eliza Evan’s work fighting fossil fuel industry infringement on land and creating the largest land art piece in existence.

Olivia Ann Carye Hallstein

Originally a printmaker, Eliza Evans now focuses on the existing imprints (both actual and abstract) and politics of the land. Transitioning from physical objects planted in the landscape, her work increasingly focuses on activism especially in land rights and mineral asset ownership. She has created opportunities for mineral rights ownership as a group to form solidarity projects to provide land rights from fracking exploitation and fossil fuel company extortion. Eliza explains the details of her project, her motivations and her aesthetic decisions to further promote and advocate for cooperation, interdependence, and shared governance of resources in the face of large oppressive forces.

“All the Way to Hell: Disrupt Fracking, Own Minerals” project poster

Considering the progression your work has made from sculptural objects in the land to the junction of grassroots organizing and activism, what role does social art have in your work? What is your approach?

I am a researcher and observer by inclination. My earlier works were distillations of the social and economic systems generating catastrophic loss. I've reached a point where mourning, however necessary, feels like capitulation. Whatever I put into the world is committed to resisting the systems that undermine us and contributing to conditions from which a just future can emerge.

I am a reluctant practitioner of socially engaged work. First, I'm an introvert. If I have charisma, it's a crusty one. I've said from the beginning that if I could make work anonymously, I would. But invisibility is a luxury, and these times call for something else. Second, I think there is a lot of irresponsible social practice out there. In the 1990s, I completed a PhD that required conducting fieldwork in impoverished rural areas in South Asia. The project was overseen by two chairs, a committee, the university's human subjects review board, and local researchers to protect interviewees from potential abuse. The process is imperfect, but at least there is one. I am unaware of any shared ethical standard or notion of informed consent in social practice--an art form that too often instrumentalizes the attention and labor of others.

That said, I've developed an art project, “All the Way to Hell”, that invites participants to instrumentalize themselves. By committing their name to a deed, participants are not only contributing to the creation of a collective artwork, they are registering their protest. The record of this act will be maintained for as long as property records exist. I call it the 100-year sit-in. Compared to the risks associated with other forms of climate protest and direct action, the risks are low but not zero. I try to make that clear. That this risk is shared among thousands creates its own bond or community. That's at least my hope.

Exhibited core sample taken from mineral-rich land, “All the Way to Hell”

“But invisibility is a luxury, and these times call for something else.”

I share your concerns regarding the safety and respect in social art practices and admire your dedication to agency in your projects. In "All The Way to Hell" you create a structure for land-owner solidarity in the fight to mitigate climate change. With this decentralized structure and the agency participants have, what are the inherent responsibilities related to contemporary resource ownership? And have the participants built upon the structure you have created?

There are very few resources for landowners and mineral rights owners who either have to contend with or want to resist fracking. Surprisingly, there are few mechanisms for mineral rights owners who are pro-fracking to join forces. That's how the fossil fuel industry wants it, as atomized and ignorant mineral rights owners are easier to manipulate. To say no to frackers, you have to have a lot of mineral rights (more than 600 acres). The fracker is obliged to attempt to negotiate with you, but after having spent the time and money to do so, you can be forced if other mineral rights owners sign a lease. The process is not eminent domain, but it is an analogous process.

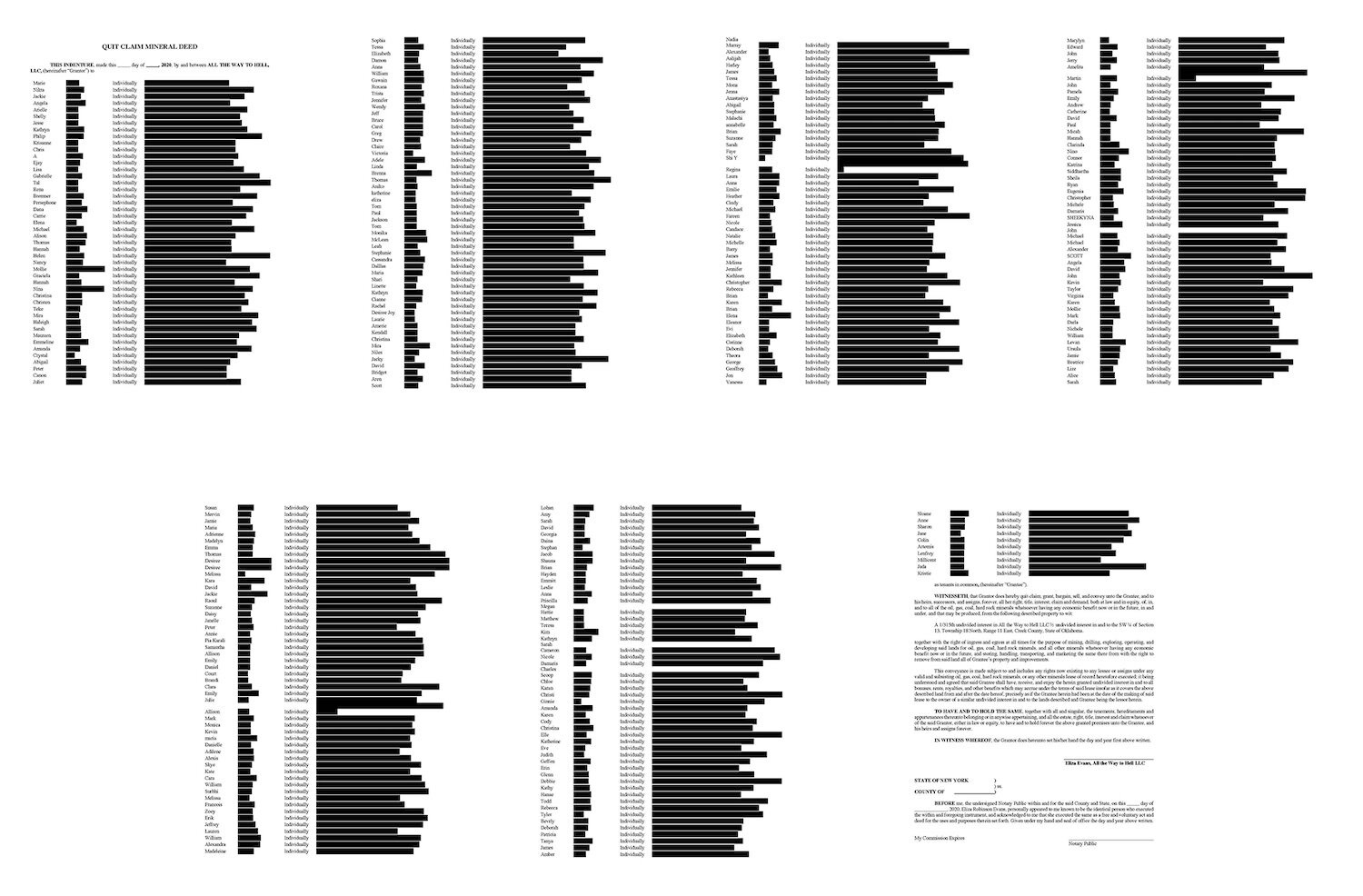

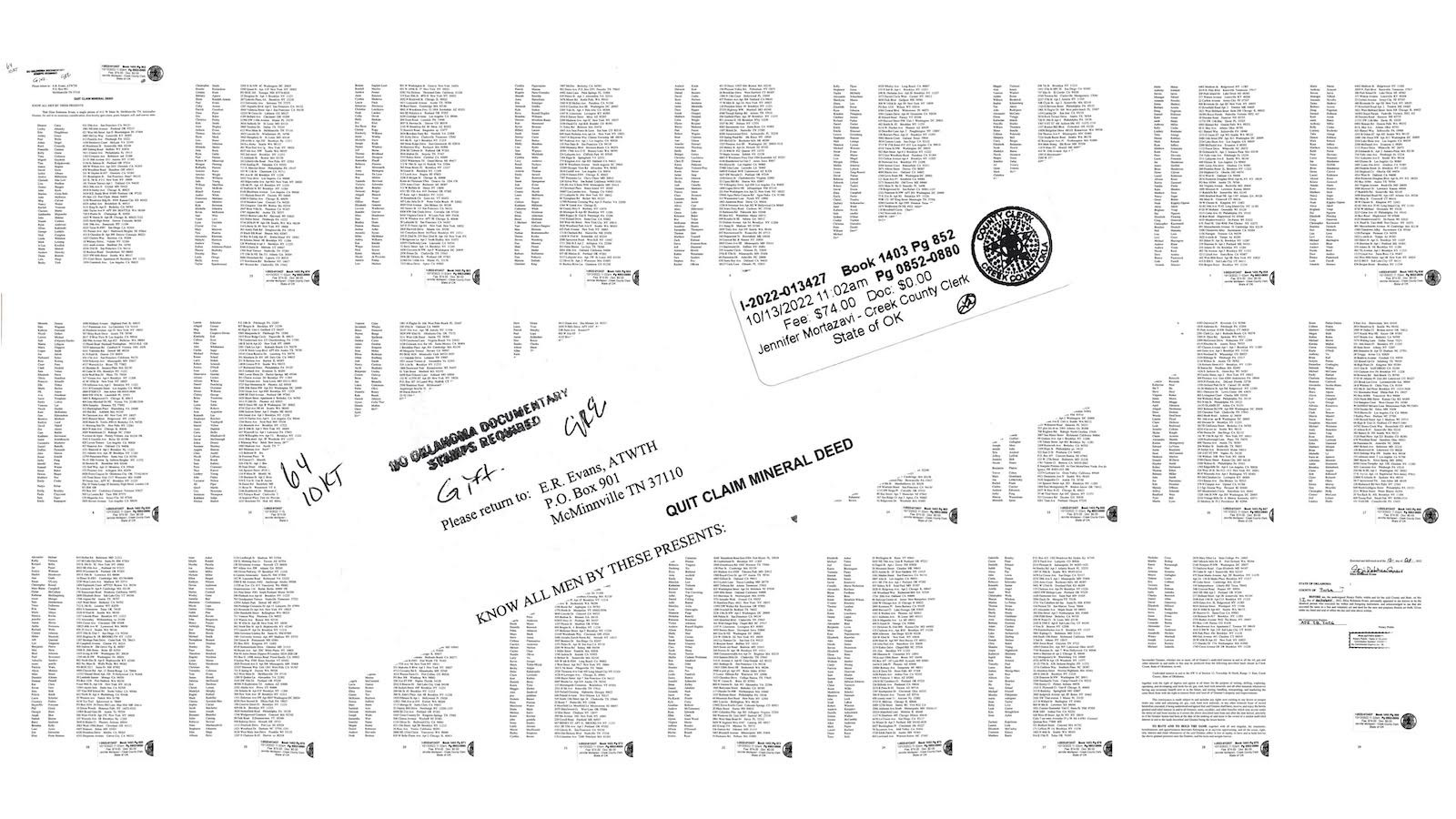

All the Way to Hell draft mineral deed: All the Way to Hell 350+ participants to date. Last names and street addresses redacted.

I am beginning to reach out to other mineral rights owners. One is in the process of giving her mineral rights to a nearby Native nation. Another owner is a Diné woman who inherited fracked mineral rights from which she receives modest royalties. She provides much-needed basic supplies for the unsheltered on the reservation and creates opportunities for Dine youth to learn and practice traditional land stewardship. Others grapple with the conflicted legacy of mineral rights but are overwhelmed by the legal and regulatory hurdles that doing anything but saying yes to frackers poses. Who feels equipped to say no to the likes of Exxon?

As intimidating as Exxon is, there are more significant issues. As the landback movement has helped us realize, everyone in the U.S. lives on stolen land. Mineral rights are a tool of colonization. In the early days of colonial settlement, ownership of mineral rights was unclear. Those rights inhere either with the state or with the property owner at different times. Ultimately, the Homestead Act resolved mineral rights in the continental U.S. by granting ownership of mineral rights to property owners to incentivize the migration of settlers away from the eastern seaboard into the interior.

I am asking mineral rights owners to reconsider their orientation to these legacies. Most individual mineral rights owners inherited the property; it may connect them to a particular place and history. But extraction from these properties is creating an entirely new planet. I'm asking mineral rights owners to do the hard thing of examining their property's history and future and be accountable for it. There is no easy solution. There is no washing of hands. It requires diligence, vigilance, and cooperation.

Eliza Evans registering Land deeds for “All the Way to Hell”

These are such important insights and corrections that I hope the larger public will be receptive to. Still, let’s transition to form: in exhibiting works related to "All The Way to Hell" you combine graphic media with infographics and physical documentation and well core samples for display. What effect has this combination of media allowed you to achieve?

I'm interested in exploration, adaptation, and giving material, nonfiction form to unhinged notions of the possible. One of my tasks as an artist is to create new ways of knowing and understanding a complex thing. The first viewer I have in mind is myself. I'm a researcher by temperament and training, so digging in will always be my first impulse. The studio work is stripping away all that is unnecessary from the accumulated data, objects, stories, etc. I'm a minimalist, so I'm looking for incisiveness, efficiency, and elegance. Sometimes I hit the mark.

Mineral rights are miles underground and inaccessible to most of us. Apart from whatever efficacy fractionalizing mineral rights into thousands of properties may have as a protest, the transfer of formal ownership via a deed creates a tangible connection between participant and mineral, experiencer and art. In theory, mineral rights extend to the center of the earth. A participant's mineral right may measure only a few square feet as represented on a cadastral map but extends three dimensionally downward for 4,000 miles. I love thinking about this sculptural space. It's outrageously grandiose. All the Way to Hell is the largest land art project in the world, yet it exists on sheets of 8 ½ x 11 paper.

“All the Way to Hell” is the largest land art project in the world, yet it exists on sheets of 8 ½ x 11 paper.

The well-core samples are extracted from the earth by fossil fuel companies at great expense. Most are kept in secure storage facilities because the data they contain is considered highly proprietary. Exhibiting the well-core samples daylights corporate secrets and grounds the spectral methane and carbon dioxide in their very material, rocky origins. I encourage viewers to touch the art when installed in less formal settings.

The values your works like "Kill Plot Home Goods", "All the Way to Hell" and "Acre" (2018) hold are reflective of an idea called the "commons". "Commons" thinking in academic writing refers to the redistribution of land and reparations to promote both equity and empowerment in planning and beyond. How do you hope these topics can be implemented further? What inspired you to take this approach to your work and assets?

Everyone I know is talking about intentional communities, land trusts, cooperatives, and solidarity economies. It's an exciting time, and there are so many experiments unfolding. Last year, I received a grant from Meta Open Arts (of all things) to research creating a crypto-enabled cooperative (called a decentralized autonomous organization - in the impossible jargon of the crypto crowd) to help manage and steward mineral rights collectively. Cooperation is hard. We need tools. That includes legal tools that recognize new organizational forms. There is so much history of people working successfully to manage resources collaboratively and justly. We need to articulate these models with the legal, economic, and social systems in which we are embedded. Where systems collide, there is usually a lot of great art.

Thank you, Eliza, this has been very inspiring and is expanding what art can do to create effective real change.

Note: this interview took place via email while Evans was artist-in-residence in the Adirondacks in September, with no internet and a 12 mile drive to the hardware store to connect.

All the Way to Hell is included in Unsettling Matter/Gaining Ground, on exhibit at the Carnegie Museum of Art through Jan. 7 in Pittsburgh. Two days are programming are scheduled for Oct 5 and 6, and admission is free on those days. Registration here