Moraine/Terminal outdoor classroom for “Over the Levee, Under the Plow,” a mobile seminar co-organized by Nicholas Brown, Ryan Griffis and Sarah Kanouse. Gathering space features banners by Dylan A.T. Miner (Metis) and a desk and library by Jon Lund, 2019.

Notes on Art and Spatial Justice

What does spatial justice look like, affirmatively - not just as the absence of injustice?

by Sarah Kanouse

This question has been ever-present for me in the past year as I’ve been on sabbatical, freed from the daily academic tasks of teaching and service to reflect on past work and plant new creative seeds. I’ve also facilitated a reading group on the concept of spatial justice for faculty across art, architecture, and law whose guiding principle has been this implicit question. It asks for a grounded definition of spatial justice, one rooted in practice as well as theory, in vision as well as critique. It asks for a utopian mode, one that academics are generally disinclined to indulge. Our reading group usually demurred from offering an affirmative vision of justice, preferring to sculpt in relief – chiseling out the injustice – rather than build with clay, shaping the moist, resistant stuff of the world into something between vision, affordance, and capability. I use these sculptural metaphors intentionally: a year’s worth of meetings on spatial justice has convinced me that art has a lot to offer in both envisioning and pursuing spatial justice.

The concept of spatial justice has intellectual roots in a particular academic tradition: Marxism as adopted since the 1960s by mostly British and American academic geographers trying to make sense of the radically “uneven development” (to borrow the title from Neil Smith’s influential book) evident in both the cities of the metropole and between the metropole and its (post-) colonies under conditions of “late” capitalism. A younger generation of Indigenous activist geographers have both used and critiqued this tradition to speak to the settler colonial dimensions of capitalist spatiality, but academic conversations around spatial justice remain boxed in by what anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli calls “settler liberalism:” the seemingly transparent and rules-based system of settler sovereignty whose asymmetrically violent outcomes can only be critiqued and/or ameliorated, but never in ways that challenge that sovereignty. However, the foundational injustice of the Anglophone settler colonies stems from the unjust occupation and expropriation of land–an occupation underwritten by the presence of non-Native people, including those who may themselves be oppressed, exploited, or historically denied personhood to begin with. True spatial justice–including for those whose very presence sustains the system which exploits us–cannot be achieved without the restoration of governance by enduring Indigenous principles, with the leadership of Indigenous people.

Beyond such general statements, a decolonial vision of spatial justice is hard to articulate and even harder to achieve. Five hundred years of colonization cannot be simply rolled back like a soiled carpet to reveal an intact “Indigenous system of governance” ready for a quick sand-and-polish. Such a unified system never existed – and wanting to implement one “at scale” may be just another way of “seeing like a [settler]” state,” to channel James C. Scott. Moreover, settler colonialism and racial capitalism are world-making and subject-making enterprises: there is no outside, or above, or below. They have done such incalculable and intentional damage to the existence of other ways of feeling, sensing, thinking, and being that many of the concepts available to organize against them are entangled to some degree. But because they are encoded, however ambivalently, in who we understand ourselves to be, the tools by which subjectivity is sculpted and expressed–art, music, literature, ritual–are indispensable to both the articulation and pursuit of spatial justice.

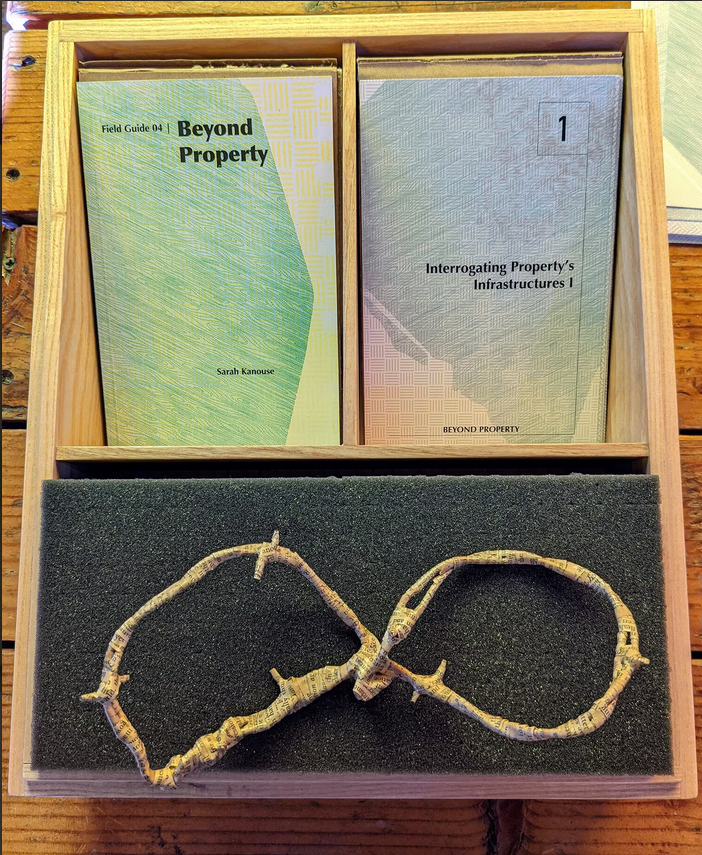

“Beyond Property” prompt cards and artists book by Sarah Kanouse for “Over the Levee, Under the Plow: an experiential curriculum, co-organized by Kanouse and Ryan Griffis, 2019-2021.

Subjectivity in the Western liberal tradition is structured around the various forms of property that arose with the modern era and are entangled with the origins of capitalism. As a primary means of mediating social relations, property divides the world into subjects and objects: subjects who have rights and objects that (largely) do not. Historically, those classified as legal or potential property - enslaved African and Native people–formed the constitutive outside of the liberal subject and, indeed, of humanity itself. The liberal subject’s political rights were initially contingent on holding property in land; later, this proprietary requirement expanded to include “property in oneself” (e.g. not being indentured or enslaved or, for many centuries, female). Enforcing private property regimes on Indigenous territory served both as a mechanism of land seizure and means of assimilation, and adopting individual ownership models (or pretending to) was at various moments a precondition for the limited forms of political recognition extended by the liberal state. Yet even though chattel slavery and Native dispossession are rightly decried by today’s adherents to the liberal political tradition, political and subjectivity is still expressed and often experienced as what C.B. McPherson classically termed “possessive individualism.” The individual artist developing a signature style that both differentiates and unifies their work to appeal to collectors exemplifies the operations of proprietary individualism in the arts. However, the model is capacious enough to include artists (like myself) differentiated as much by the critical insights we offer as the objects we produce. Under settler liberalism, property–in its many and shifting forms–has become the relation that structures all other relations, the primary means of self- and community actualization, the dominant way of relating to self and world.

Holding liberalism to its aspirational values has helped to move ever more entities from the ‘object’ to the ‘subject’ side of the ledger, and increasingly immaterial forms of “proprietary interest” allow newly acknowledged subjects to exercise agency, as the “rights of nature” movement is attempting to do. For an Indigenous tribe to successfully sue for the return of land lost through treaty abrogation, for a Black family dispossessed by urban renewal to receive compensation, for a court to recognize a river’s possessive interest in remaining unpolluted–these are stunning victories for spatial justice within the paradigm of the liberal settler state. And yet they also shore up property and proprietary liberalism as solutions to the problems they created, a colonial tautology that gets us ever further from the vision of the settler state’s eventual replacement with a system of governance based on enduring Indigenous principles, under the leadership of Indigenous people.

Such a vision cannot be crafted only by artists, particularly artists as recognized within settler liberalism. But we are skilled in crafting aesthetic experiences where recognition and, alternatively, disidentification are possible. By making public our efforts to disentangle from proprietary subjectivity–particularly through relational accountability and active engagement with Indigenous leadership–we can contribute to a broader cultural shift. Moreover, my conversations with social-justice academics and movement-based activists over the last year have convinced me that art and artists have something to offer beyond the vague (if essential) work of “imagining otherwise” or “shifting the narrative.” By both training and orientation, we understand that tools shape both process and outcome: they make worlds while meeting goals. This insight is as true for the tools of law, activism, and policy as it is for more conventional creative tools. Thinking both reflexively and improvisationally about methods allows us to respond to the world that our actions are shaping, not just to the one we seek to replace.

Some of the most visionary and effective projects advancing decolonial visions of spatial justice have been developed as community-focused collaborations involving lawyers, activists, artists and culture bearers. Programs, like the Oakland, CA-based Shuumi, ask non-Indigenous people to pay a voluntary “tax” to Indigenous-led organizations as a means of recognizing Native sovereignty and building capacity for land rematriation. Although legible within the settler-colonial framework of property taxes, the contributions also reflect the payment of tribute as a form of sovereign recognition, as practiced by many tribes prior to colonization. At least a half-dozen similar programs have launched across the United States. New community land trusts are forming that return land to Indigenous control while also meeting the needs of diverse communities for food and housing. Recognizing that Indigenous stewardship is the most effective means of environmental protection, property owners are donating land to Native-led land trusts at ever-greater numbers; such transfers are an opportunity to write into the title deed language acknowledging the colonial dimensions of ownership while taking them off the speculative real estate market forever. Other individuals and nonprofits are creatively using the “easements” of settler property law to permanently safeguard Indigenous stewardship and access to culturally significant landscapes. In Washington, a new spirit easement campaign asks property owners to permanently codify a welcome to the spirits of Indigenous Methow ancestors with the Registrar of Deeds. While this particular easement appears largely symbolic, it reflects a broader collective effort to sustain other ways of living in and with the land, incommensurable with Western cosmology. These and other efforts may not “look like” art in the traditional sense (indeed, they might look more like a title search), but they get us involved in the messy, halting, uncertain work of aligning the systems that govern of our lives with a broader, decolonial vision of justice.

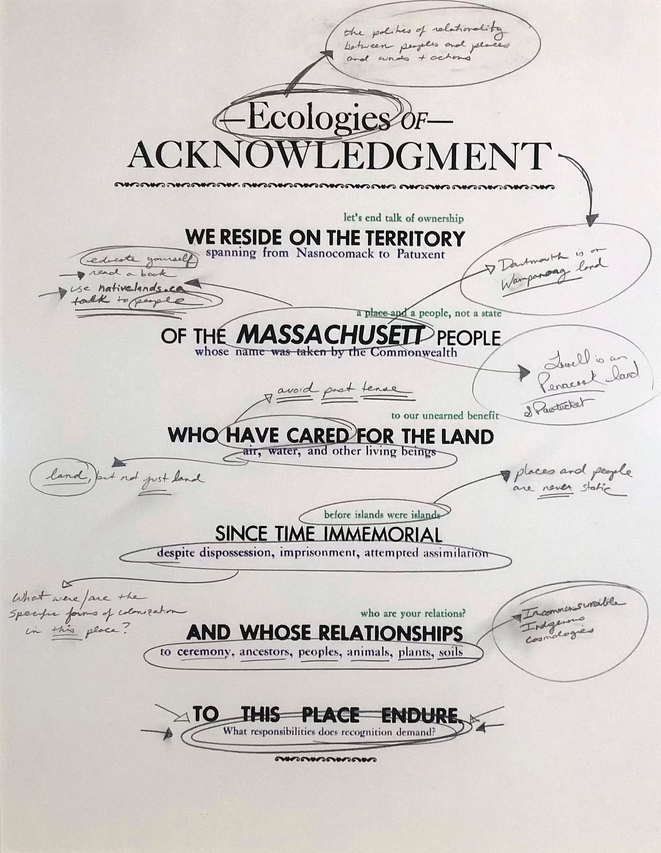

“Ecologies of Acknowledgment” letterpress print with text by Nicholas Brown, Sarah Kanouse and Elizabeth Solomon (Massachusetts), printed at Huskiana Press by David Medina, 2019.

Click images for more information