“Sculpture to Transform Culture into Nature,” street infrastructure displayed with regrowth, Mark Brest van Kempen

Passive Resistance: Artists stand back and watch their work grow

Reflections on Growth with Jen Urso and Mark Brest van Kempen

An interview by Olivia Ann Carye Hallstein

Jen Urso and Mark Brest van Kempen parallel each other in topics related to social and personal healing that is deeply connected to their surrounding localities and the natural world. Mark approaches these themes by directly integrating his grassroots organizing and the literal weight and materials of infrastructure and the natural world to display the wounds and growth of human influence. Jen takes a deeply personal perspective, exploring the literal edges of her person and psyche in lines and forms reflecting on locality. Their work is currently showing in the exhibition “Modern Desert Markings: An Homage to Las Vegas Area Land Art” at the Marjorie Barrick Museum of Art at UNLV in Nevada, which is simultaneous to the controversial land-art fair “Desert X” in Southern California.

Jen Urso, “What the Desert Already Has,” 2023, terrarium with native desert growth, included in Modern Desert Markings.

Mark, your contribution to the “Modern Desert Markings” exhibition at UNLV will follow a theme of environmental wounding and healing in conversation with De Maria’s “Las Vegas Piece” (1969). Much of your work has related to bioremediation from industrial and human influences such as “Biolabyrinth” or “Floating Marshes”. Since De Maria made his marks using a bulldozer that had lasting effects on the otherwise untouched landscape at the time: are you planning an intervention of your own through native species landscape rehabilitation? How do these parallels play out in this landscape for you?

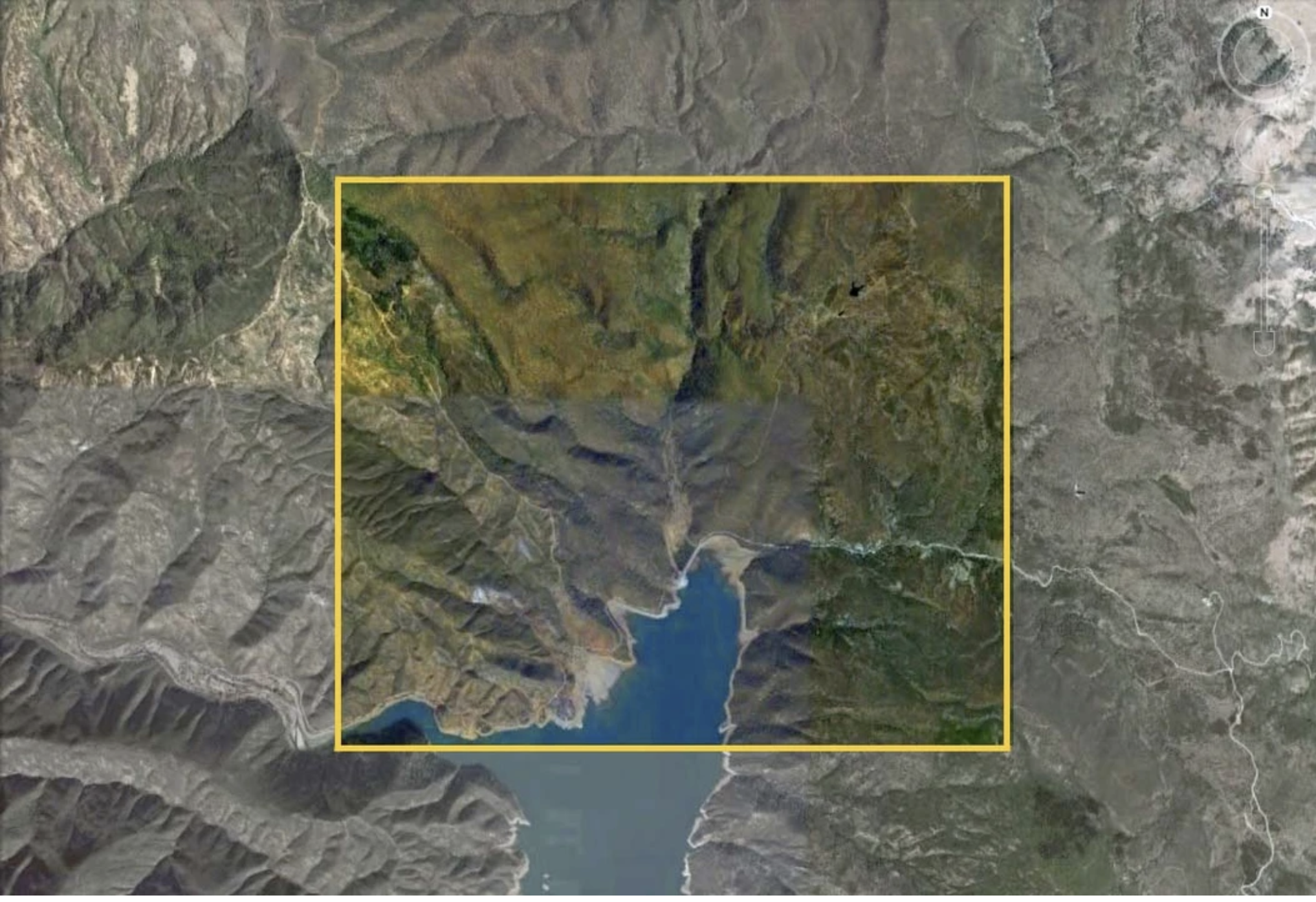

MBvK: My approach to working with landscape varies considerably depending on whether I am working with a human-altered site or a “natural” site. In the case of this dialogue with De Maria’s work, I am not only interested in the initial sculptural gesture of De Maria, but I am also interested in the intervening encroachment of the surrounding landscape that is erasing this initial gesture quickly. Within the fifty-odd years since De Maria made the piece, the actions of weather and plant growth have made the piece very hard to find and, in some areas, completely erased it. This rebounding of desert life (without any help from me) is inspiring and speaks to the temporary quality of all human activities no matter how large and aggressive. Therefore, I feel that is enough to point out this ‘healing’, overriding ability of nature without help from me.

It is interesting to visit these earthworks and consider the work of the landscape on the pieces as part of the work. Most people only see photographs of these pieces that were taken when the pieces were first completed with crisp edges. Now just a few years later the pieces have completely disappeared or are quickly eroding. I recently visited Double Negative and I would argue that the erosion is as striking as Heizer’s initial massive gesture. In a few hundred years the piece will be completely gone, while I imagine that the Mona Lisa or Pieta will still be intact.

Mark Brest van Kempen, “Living from Land”, full immersion land project performance

You both certainly have this interest in human-influence and ephemerality in common, though your processes are so different.

Jen, in many of your performative interventions, you display interactions and experiences through drawn media and other forms of line work and relate this to human connection. How does the extraordinary desert landscape influence your practice?

JU: In drawing, I am more interested in capturing movement and change. No matter what you are drawing, it is never the same each time you draw it. This is either because you have changed your experience with it or the thing itself is older, decaying, eroding or moving. Regardless of what climate or environment I’m in, my work is subject to the same forces of time and change. The desert influences my drawing less and influences my sense of tenacity and resilience more. Even in the smallest sidewalk cracks and untreated land, desert plants will find a way to survive and thrive. They have built defenses like hard exteriors, thorns or bulbous water repositories. I see the parallel here with my own survival and ability to thrive despite not being raised with what many others would consider essential. The desert’s biome doesn’t consider itself to be lacking because it is all it has ever known.

Jen Urso, “Measuring Coastline,” drawing using composted remains of the artist’s sister

I am so glad you mentioned resilience, plant life, and the deep psychological connection our “Daseins” (senses of self) have with the landscape.

Jen, you explored this in your “Coastlines” project, no?

JU: Yes, the “Measuring the Coastline” piece uses the term “coastline” to refer to the concept in fractal geometry where the closer you investigate or measure a coastline, the longer it becomes. This is related to the crevices and details of an edge and how, as you look closer, there is always more detail to see. After so many changes from the introspection that came during my sister’s illness and her death, I wanted a way to measure it irrationally. So, I thought of myself as a coastline or a country where someone was trying to map the edges. Each time I looked closer, I imagined my edges would expand. My goal was to have a direct, sensory experience with my sister by using her composted remains to dust around the edges of my body, showing my actual form meeting with what was left of hers.

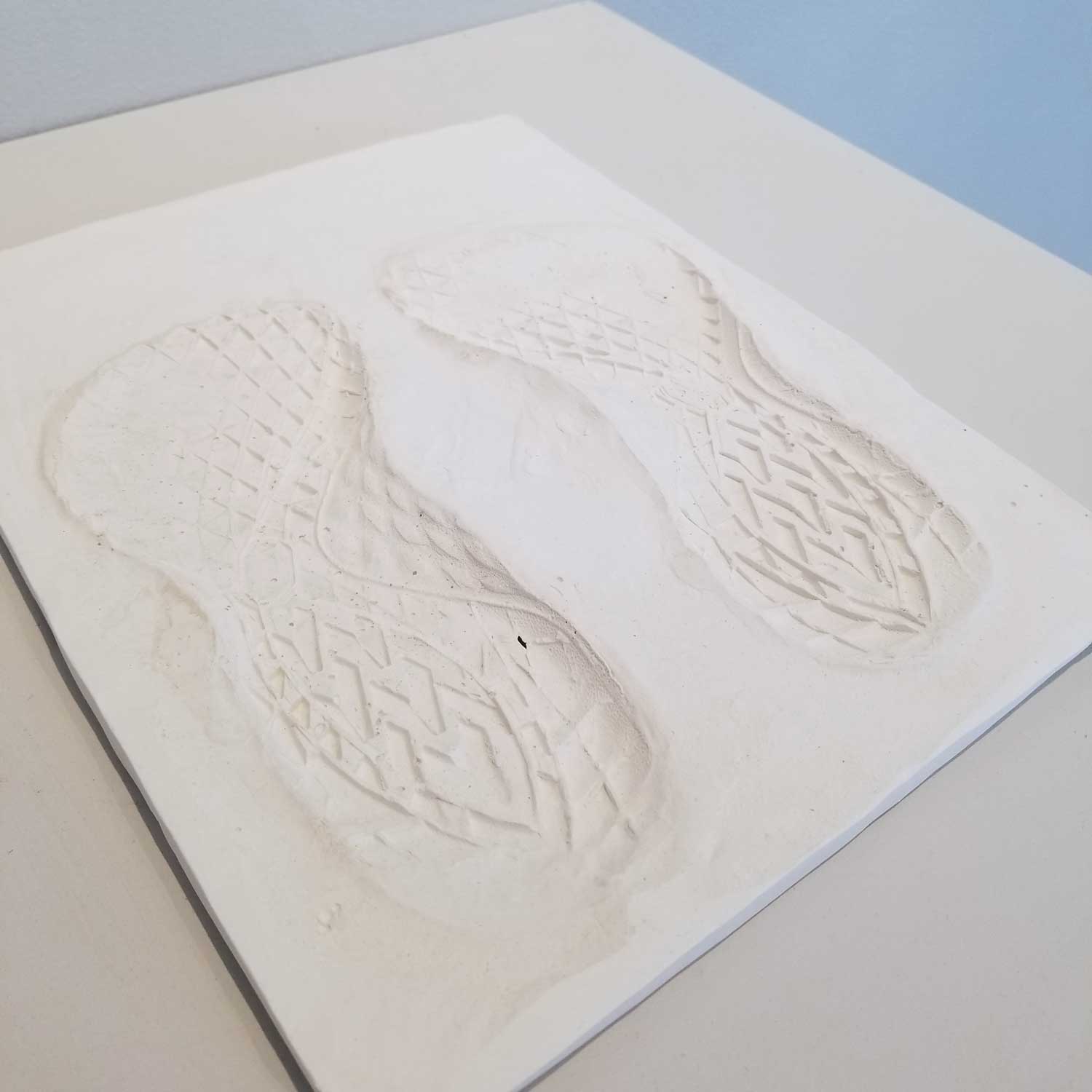

Mark Brest van Kempen, “Transnational Footprints”

That is so touching and heart-wrenching, Jen.

Mark, you share this interest in the personal becoming political through your interwoven approach to art practice as an extension of your life and activism directly like “Living from the Land” Your work seems to stand at a conjunction between grassroots community organizing and material activation to contend with and often correct human influence in the natural environment. Where does art end and your life begin? Is there a difference? And what is the role of material creation as a result of your activities?

MBvK: To me art should be a verb just like living is a verb. To say that art is an object is like saying that music is a piano.

I think art at its most basic form is a human communicating their perception. Perception is being in a place, and sensing that place with your body. Bodies sensing in space is what we are. When I first let go of traditional art materials like paint and canvas, that’s where I landed. I said to myself “I am a body in this place, so these are the tools and materials I will use to make my art.” “Living From Land” was very related to landscape painting, but instead of standing outside of the picture and representing it with paint, I stood inside the image and represented it by eating it with my body. I think this approach often pushes art and life closer together, but the art is framed in a way that differentiates it from the rest of life.

Jen Urso, “Measuring Coastline,” drawing using composted remains of the artist’s sister

I love a lot of very traditionally produced art and material objects can convey powerful feelings and ideas, but I also think that you don’t necessarily need objects for an art experience.

When I approach a site, I consider everything that I can about it. That includes humans interacting with places. Sometimes humans interact physically with a landscape and sometimes they interact conceptually by creating laws, rules and traditions associated with places. Private property, political borders, laws that apply within one boundary and not in another are all interesting “materials” for me to work with as sculpture. The “Free Speech Monument”, “Leona Quarry Earthwork” and “Benicia Tryptic” are a few examples of projects that have included people and political processes as material.

Soil as a material is rich with cultural and political meaning. We grow our food from soil, laws become embedded in soil, identities are associated with soil and our bodies ultimately become soil. Being so loaded is an amazing material to work with.

Speaking of soil and human influence: Desert X is happening simultaneously to the group exhibition you are in at UNLV. Many of the topics are socially nuanced sculptures amidst the desert landscape in both shows.

Jen, Your work is intimately tied to the people you interact with and in Arizona, where you live, has been a controversial player in migration politics. How are you integrating migration and native rights topics into your own work? How do you see the desert landscape as reflective of social interfaces?

JU: The Phoenix area has a rich history of agriculture and settlements that can be traced back at least 1,500 years. In learning some of the ethnobotany of this place, I have learned how much indigenous knowledge has been squandered and destroyed. Those who moved here believed that controlling the environment was paramount. My process in my life and in my work has been to trust the place I am in to slowly teach me what I need to know. By observing and responding, I am trying to elicit a back-and-forth with my work where I set frameworks while giving up control.

Jen Urso, “What the Desert Already Has,” 2023, terrarium with native desert growth, included in Modern Desert Markings

Jen Urso, “What the Desert Already Has,” 2023, terrarium with native desert growth, included in Modern Desert Markings

This absolutely parallels Mark’s current theme of “environmental wounding and healing.”

Mark, what is your reaction to social parallels in the Desert X exhibition? What is your reaction to the physical effects on the environment related to viewership and their transport?

MBvK: I think if the work reveals a deeper appreciation and understanding of the landscape for viewers it is generally a good thing. If it is only an opportunity for a selfie and a post on social media proving that you went to an event, obviously this is an exploitation of the landscape. Desert X, like the rest of the art world, is a mixture of opportunities for great reflection and superficial posturing. More generally about travelling and keeping track of carbon footprints, I think it is important to understand the complex problems associated with being a part of a huge, industrialized society. It is crucial to be looking clearly at how our actions are impacting the world and try to move in a more positive direction. At the same time, we shouldn’t be paralyzed by an impossible desire to be perfect. This usually leads to despair and giving up. I think it is more valuable for us to move imperfectly towards an ideal but continue it for a lifetime.

Mark Brest van Kempen, “Living from Land”

Mark Brest van Kempen, “Living from Land”