Artist during field research in desert

Retracing the Paths of the Planet:

Katrina Bello’s process, reflections, and intimacy with the world through drawing

Interview by Olivia Ann Carye Hallstein

Katrina Bello’s artwork begins far outside the walls of her studio. She revisits physical, intellectual, and emotional landscapes through a touching example of experiential fieldwork. Combined with informed philosophical questions and insights and an in-depth understanding of the physical world and its textures, she uses drawing as an intermediary between herself and this world. Everything from the physicality of her process to her choice of scale and subject are intentional and steeped in perception. She is a fantastic example of an artist whose work is an interwoven extension of her very sense of being.

From “Drawing as a Noun, Drawing as a Verb”, Modeka Art, Phillipines, 2021

Katrina, in your work, you create hyper-realistic surveys of the natural world, often of water, tree bark, and rocks. What is it about your process that helps create this intimate connection between yourself and your subject?

I think the textures in my work result from my studio process that has a heavy involvement with the sense of touch. Part of my work process is hiking and photographing for references for the drawings; during this activity I am constantly touching the things I encounter so I can observe them closely and see the details of the tree bark, the rocks, the water, and the desert canyon walls.

The role that touch plays in my work was something I did not examine until it was pointed out to me by the graduate school director at MICA. Her name is Zlata Baum and she recommended I read a particular text by Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa titled “Eyes of The Skin: Architecture and The Senses”. The text shed light on what I felt I was doing. In the text, Pallasmaa mentions touch as the “mother of the senses.” In the book’s introduction, he wrote: “Touch is the sensory mode that integrates our experience of the world with ourselves…My body is truly the navel of my world, not in the sense of the viewing point of the central perspective, but as the very locus of reference, memory, imagination and integration.”

More than simply finding references for my work, it is my process of knowing and having a deeper connection to the place that makes it unique. In this intimate process I become aware of the textures of things. Even in my studio process, while drawing, touch also plays a large role. For example, my drawings are made with soft pastels that I crush into a powder, which I then apply on the paper with my hands rubbing the powder vigorously with my palms on the papers surface and using my fingertips to make details.

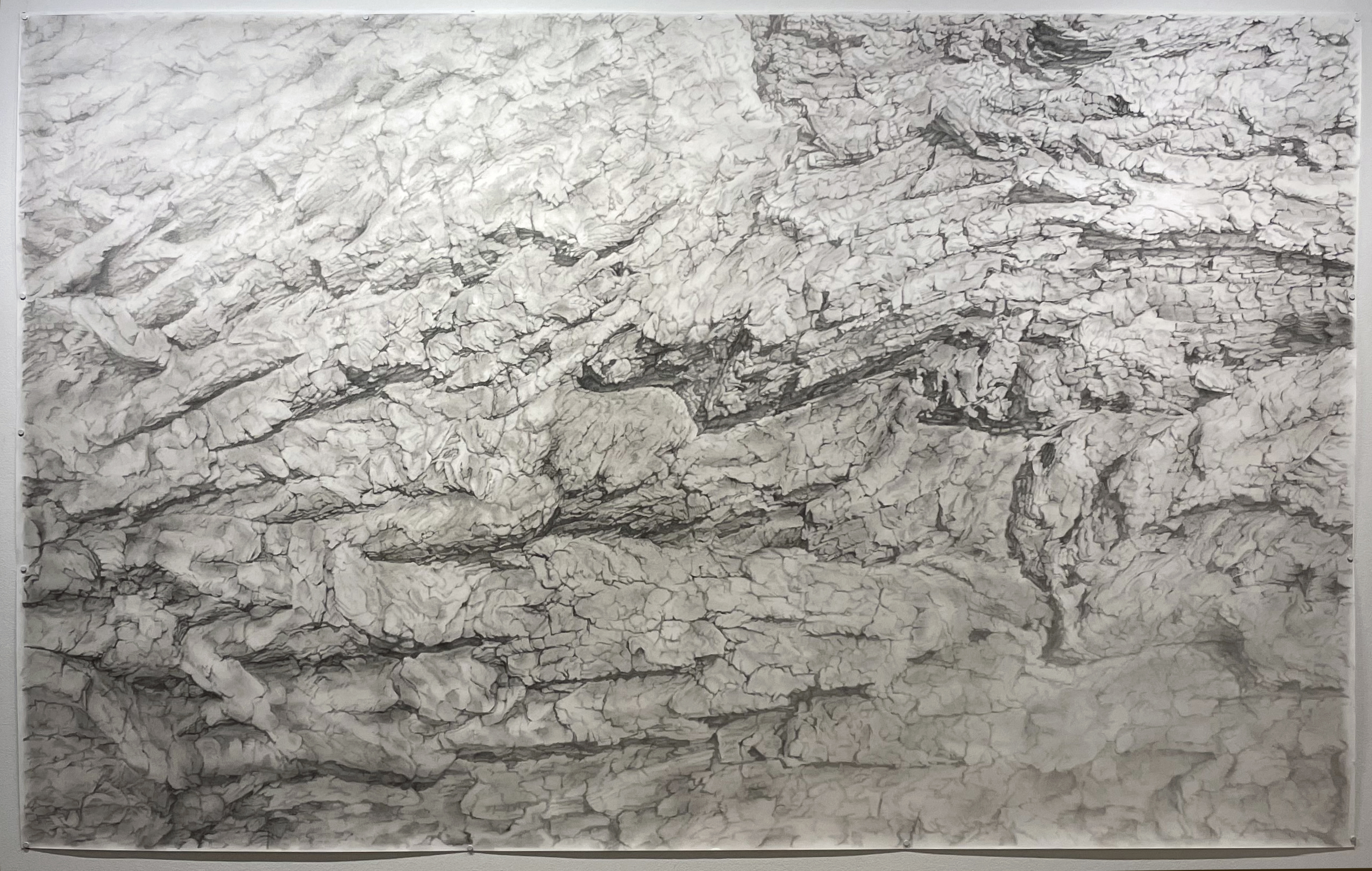

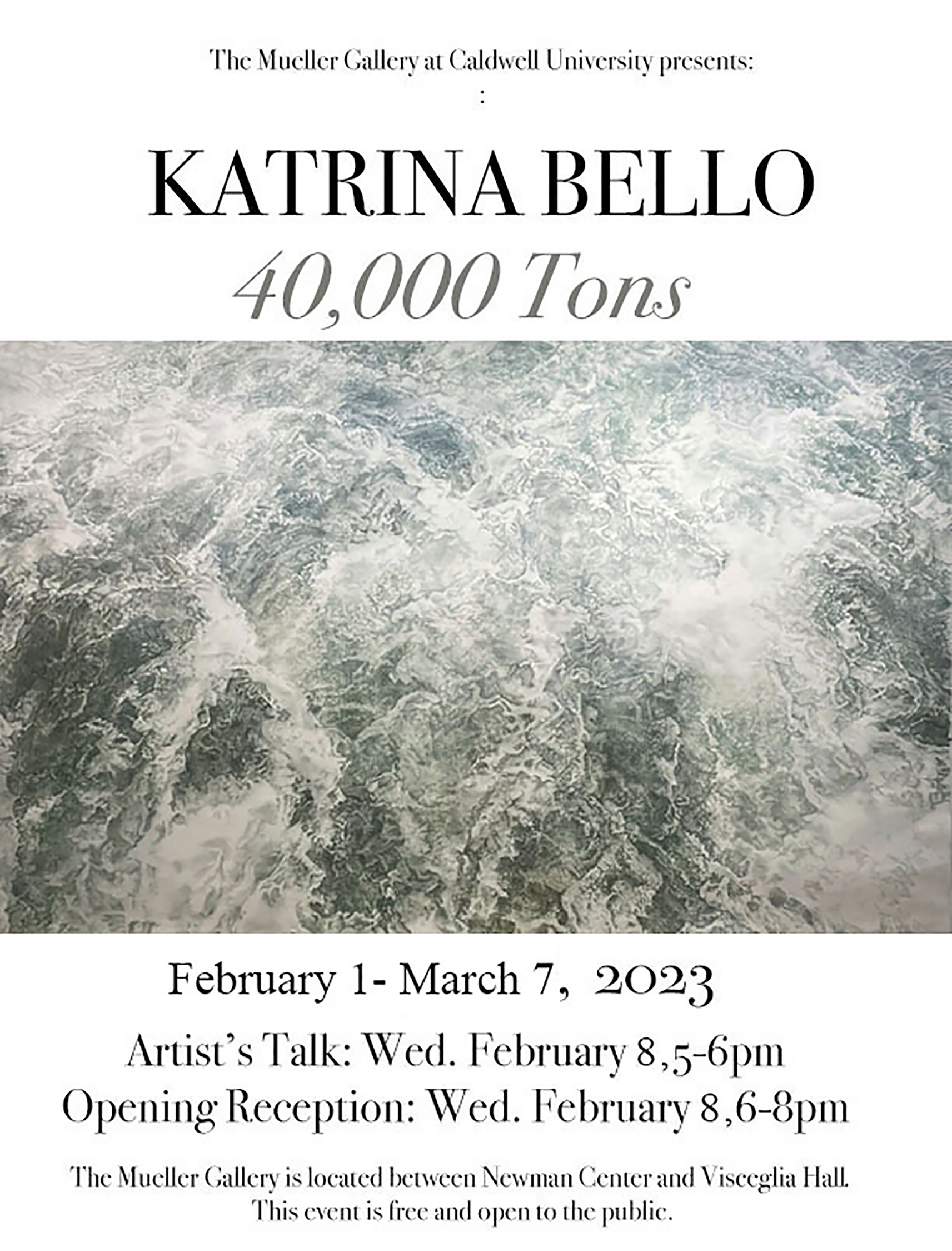

From “40,000 Tons”, Caldwell University, New Jersey, 2023

More than simply finding references for my work, it is my process of knowing and having a deeper connection to the place that makes it unique.

Your process makes sense to me and how I experience your work. When I look at your work, it brings me an incredible stillness; a similar feeling that I have when, lost deep in thought. I find myself sitting peacefully as time flows freely past me. There has also been a lot of discussion in my circles about the histories and identities that materials and objects themselves hold. What do you consider the relationship between material, identity, and experience?

I am very grateful when my work evokes a sense of stillness in someone. Stillness is not a quality that I intentionally work to create, but because the work takes a great amount of time to execute. The process of making the small details, especially the large drawings, often necessitates that I am sitting and standing still for hours. Perhaps these are somehow embedded and revealed in the work. I find the relationship between material, identity and experience as something that is forged, informed, and understood through lived experience and knowledge. One of the questions that had occupied my thoughts in my studio practice was “how do I know what I know” and how my work is forged by what I know. A few years ago, I came across a text that lists the main sources of knowledge: memory, senses, rational thought, testimony of others, and revelation.

Time is also an idea that occupies my thoughts when I am working, so perhaps that also permeates the work as well. I think of the contradiction between the human experience of time through minutes and years, while rocks and mountains experience time in epochs and eons. And when I observe the tiny lines that look like drawings in the cracks and fissures in tree bark and rocks, I feel a sense of wonder for the length of time during which such lines developed. This stands in contradiction to the speed through which I make a line with my pencil on the paper. I am confounded by the seeming stillness of these linear patterns found in nature, which are signs of an ongoing yet barely perceptible movement and transformation that is taking place. Therefore, when I am in my studio making a line drawing that takes months to almost a whole year to execute, I feel like I am retracing or reenacting the slow geologic time that these lines in nature occurred.

Artist in studio during artist residency at Brush Creek Founation, Saratoga, Wyoming, 2018

…when I am in my studio making a line drawing that takes months to almost a whole year to execute, I feel like I am retracing or reenacting the slow geologic time that these lines in nature occurred.

And, those lines are compositionally fascinating as well! Though your work is based in intensive observation, your compositions sit at the intersection of realism and abstraction. The pieces I have seen, interface and permeate between topics of artistic materialness, and the actual physical patterns of the world. Is there a correlation for you between abstract reflection and a literal understanding of the landscapes we inhabit?

I think of abstraction in the planning and composition of my drawings. At the same time, when I am executing the drawings, I am constantly thinking of realism when it comes to the details of the rocks, tree bark, and textures of the landscapes that these subjects are part of. My engagement with nature often entails up-close observation. And when I do so, I often find what appears like miniature terrains on the surfaces of rocks and tree bark. I am fascinated by how they seem alien, otherworldly, and remote.

I am more interested in the desire to trace the lines of these otherworldly forms, and draw them as they appear, rather than invest in the desire to reinvent them. This “otherness” in things that is manifested in their surfaces and patterns is an idea that I became interested in after I came across a 2007 lecture on the works by Gilles Deleuze of philosopher Manuel de Landa at the European Graduate School. In the lecture, de Landa spoke of Deleuze’s studies on nonhuman expressivity. He gave examples such as crystals, rock striations and geological events like volcanic explosions and tectonic plate movements that dramatically change our landscape in very slow times scales; these are all part of the idea that expressivity is not solely possessed by humans, and that even inorganic things have the capacity to express their identity through their forms. De Landa further explains that for Deleuze, if we focus only on things that are human and the creations by humans, we lose sense of our “otherness” which refers to the nonhuman.

These ideas about nonhuman expressivity and otherness were such significant revelations for me. It made me reexamine how I perceive the natural world and how to represent it in my work, especially in my drawings. It taught me to “re-see” forms in nature as marks, paths, and imprints of purposeful processes that lead to their construction. It led me to reconsider working with realism, literal representations and understandings of the landscapes we inhabit.

Salix, 2017, charcoal and pastel on paper, 60 x 92 inches

… even inorganic things have the capacity to express their identity through their forms.

I love how considerate you are of perception relating to your subject. And you express this very intentionally through your formatting. You are very considerate when choosing the scale of your artworks, presenting either monumental 5 ft x 8ft or delicate and intimate 5 in x 8 in pieces. How did you decide to choose specifically these scales? What is it about these two extremes that you want to emphasize to your audience?

I am interested in these extremes in scale as reflections on the sense of scale that is implied in the subjects of the works themselves. Because my subjects are nature, the environment, migration, and my memories and experiences of landscapes that I have physically encountered. I often feel that there’s an overwhelming sense of boundlessness in these subjects- that they are ungraspable; especially when it comes to memory. Just as a desert or body of water can feel vast and enormous, so do the scale of environmental issues that we are currently dealing with such as global warming, ocean pollution, deforestation, and more.

At the same time, I also make the opposite: very small things that are intended to communicate intimacy and fragility. When I make very small drawings based on oceans and landscapes that can fit in the palm of one’s hands. It is intended to communicate the sense that it is fragile, precious and something to care for. Therefore, I count on size and scale to insist on themes that have an urgency (such as the ones relating to the environment) within the subject of the work.

Hawak/Hold: Passamaquoddy Bay, 2019, still image from video animation

I often feel that there’s an overwhelming sense of boundlessness in these subjects that they are ungraspable; especially when it comes to memory.

You mentioned a combination of literal physical reflection and personal experience. From what I understand, the topics you choose to depict are related to your own migration story. What was it about your own migration that inspired this reflective and structured practice?

I feel that my experience of the landscapes here in the United States is through the lens or spirit of exploration, with a little bit of longing for the remembered landscapes of my native country. The more I live here, in my adopted country, the more it seems like my memories of my migration experience are embedded in the work. When I migrated to the United States, it was unexpected, and I was not prepared to leave my native country. I had an intensely strong connection to the landscapes of the city of my birth, which is located in the southern part of the Philippines. The tropical coastal city I was born in lies at the foot of the largest volcano in the country that is presumably extinct, and the city has a beach with black sand made from eroded volcanic material. My siblings and I spent our youth mostly exploring the tropical outdoors, especially this black sand beach and a sea that is darkened by that sand.

Immensity (Smudge), 2019, charcoal and pastel on paper, 60 x 37 inches

As my memories of this landscape begin to fade as I get older and live longer here in the United States, I notice that my work begins to have a sense of that landscape more and more; my drawing works became larger, more detailed, and with color resembling the color of the dark sand. Perhaps this development of my work is attributed to longing and nostalgia.

At the same time, the work is made with an intense interest and fascination with the landscapes of my adopted country. I am especially interested in exploring tree species that are so different from those in the Philippines, and mountains and deserts that I have never seen until coming into the United States.

My landscape exploration here in the United States started in New Jersey. This was the second state I lived in here; New York was where I first lived when I migrated. I was first interested in the trees near where I lived and often photographed and observed them through the years. From there, I started becoming interested in rocks, trees, ocean waters, and mountains in places I traveled to as a tourist and as an artist-in-residence.

My drawing works became larger, more detailed, and with color resembling the color of the dark sand (of my birth landscape). Perhaps this development of my work is attributed to longing and nostalgia.

I can see a parallel to your process with charcoal dust in your hands, the volcanic soil, new landscapes, and the subject of your new work. Your recent exhibition “40,000 Tons” at the Mueller Gallery at Caldwell University, expanded your earthbound topics to astrological ones. “40,000 Tons” is the amount of stardust that falls to earth each year, correct? What has inspired you to focus on stardust and abiogenesis (the origin of evolutionary life on Earth)?

Correct. According to a 2015 feature in National Geographic, that is the volume of cosmic dust that falls on Earth annually from space. My interest in looking into space subjects emerged during the lockdown during the early part of the pandemic in 2020 when I was unable to travel to the Nevada desert where I intended to photograph and observe rocks for a series of drawings and videos. Before the pandemic, the objects and landscapes referenced for my work were things and places I had physically visited, observed, and photographed repeatedly through several years. But when the pandemic started, I had to find ways to make up for my inability to travel.

Then, in May 2020, the world was captivated by the first launch of NASA astronauts into space by SpaceX. During those days around the launch, it felt as if the whole world stood still and was looking upwards to the skies and outside of Earth. It was for me a realization of how the entirety of my studio practice was focused on mostly looking into the natural world that is limited to Earth, even though I was thinking of vastness.

It was for me the beginning of thinking of the exponentially rich, expansive and vast resource of matter, time and astronomical events outside of Earth. And when I began to work with this new resource, my research reached a point of learning about the formation of how the planet, and everything in it, even the thoughts and emotions we feel, emerged from the matter that comes from space. I was fixated with the volume of this matter - this 40,000 tons of cosmic material that falls annually. So, when I am working with drawings using soft pastel powder and rubbing these pigments with my hands on a five by eight foot expanse of paper, sometimes I feel like I am retracing the path that cosmic dust is traveling on the planet.

Sometimes I feel like I am retracing the path that the cosmic dust is traveling on the planet.

Thank you, Katrina, for a truly perceptive interview. You have given me a lot to think about and broadened my perspective on the world.

40,000 Tons has been extend at the Mueller Gallery until March 7 here