Gene A. Felice II, Jennifer Parker, and Juniper Harrower

Visions of Algae, installation views, 2022.

Photos : Bradley Pierce, UNCW, courtesy of Cameron Art Museum

The Algae Society just finished a run of two exhibitions. The Confluence exhibition at the Cameron Arts Museum in Wilmington, North Carolina, January 28 – April 24, 2022 featured sculptural, interactive works, video projections, kinetic works, and rapid prototyping, all featuring algae from the microscopic scale of phytoplankton to the giant kelp forests of the Pacific Northwest and the Confluir Exhibition at the Facultad de Bellas Artes Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Sala de Exposiciones del Salon de Actos Feb 9th-March 9th 2022.

The Algae Society embraces a sustainable and equitable path for human+algal relationships and the complex roles in climate change these are manifesting. In this interview Ken Rinaldo chats with members about the Algae Society and their formation and approaches as well as recent curatorial adventures.

Questions: by Ken Rinaldo

Where did you meet, and how did the Algae Society come together with its members? How many members are there, and who are they?

Jennifer Parker: The majority of the Algae Society members worked with me in the OpenLab collaborative research center when they were graduate students at the University of California Santa Cruz. Gene Felice was part of a larger project that I was working on in 2012 called Blue Trail in San Francisco. Gene pitched an idea to work with phytoplankton as part of that initiative known as Oceanic Scales and everything sort of evolved from there. Gene and I worked together for about four years on Oceanic Scales and then when we had an opportunity to exhibit in a children’s museum in southern California, we took the foundation of what we had been building and opened it up to other members and then new connections opened and more people joined to form The Algae Society as we know it today.

Gene Felice: Our full members list can be viewed here: http://algaesociety.org/about-3/ Our core group is made up of seven members from around the globe that have been collaborating for the past three years. Our collaborative group has grown organically, starting with the initial members that Jennifer brought together and then additional members either finding us online or being friends or a colleague of another member with similar interests in algae within the arts & sciences. Over the past five years, we have shared vocabularies, built trust and learned from each other while navigating the challenges of creating collaborative, art & science focused art across international borders.

What do artists and scientists need to learn from each other, what did you feel you learned in this experience, and what realizations do you think the scientists have discovered? Can you give me examples?

Dr. Juniper Harrower: I think art as science communication is fun and interesting, but falls short of what can be accomplished if we are talking about structural or institutional changes. Another common issue that comes up is art in the service of science, artists often becoming a hired hand or general PR for science and feeling obliged to create art that the scientist or institution approves of. While artists can engage in early stage R&D with science experiments and come up with some interesting questions or approaches they also really lack the fundamental skills and language to engage deeply with science methodology that people spend decades wrapping their heads around within their scientific discipline. I also see that many artists generally misunderstand what science even is as a discipline (and what scientists do) and scientists often greatly simplify what the arts has to offer as a research path, so there are misconceptions that are to be expected within each of the different disciplines. This can sometimes result in artists misinterpreting or simplifying systems or stories in ways that frustrate the science community and then makes them dismissive of art as a research practice. But artists can ask questions that are not considered by scientists or can dig into institutional dynamics, question power structures, problematize the western scientific approach, and approach meaning making in ways that scientists do not have skill sets for. Artists can reframe and bring attention to different ways of thinking and knowing beings, communities, and ecological spaces that science methodology does not make space for, and draw attention to modes of questioning and scientific methodologies that are flawed as an approach to respecting life forms. I am also interested in the slippage between science and mysticism and the interesting spaces that can arise when we consider the search for "objective" truths in science (who's truth?) and the methods with which we look for them as we try to make sense of life on this planet.

I think there is a lot of emphasis put on identifying how the arts has/can measurably impact science, like examples of artist interventions that led shifts in the way that a scientist approached a project. While there are those examples out there, I think the much more interesting potential (and really the long game) comes in how an artistic approach to understanding and thinking about the world could fundamentally alter how the scientific community approaches working with life and beings. Ethics and representation, and how to consider histories of oppression and violence that form the discipline of science. Rethinking the "science gaze".

I think the algae society is just starting to lean more into some of these questions - like what does it mean to actually collaborate with other organisms in respectful ways? - and that the work will continue to get even more exciting as we continue to grow!

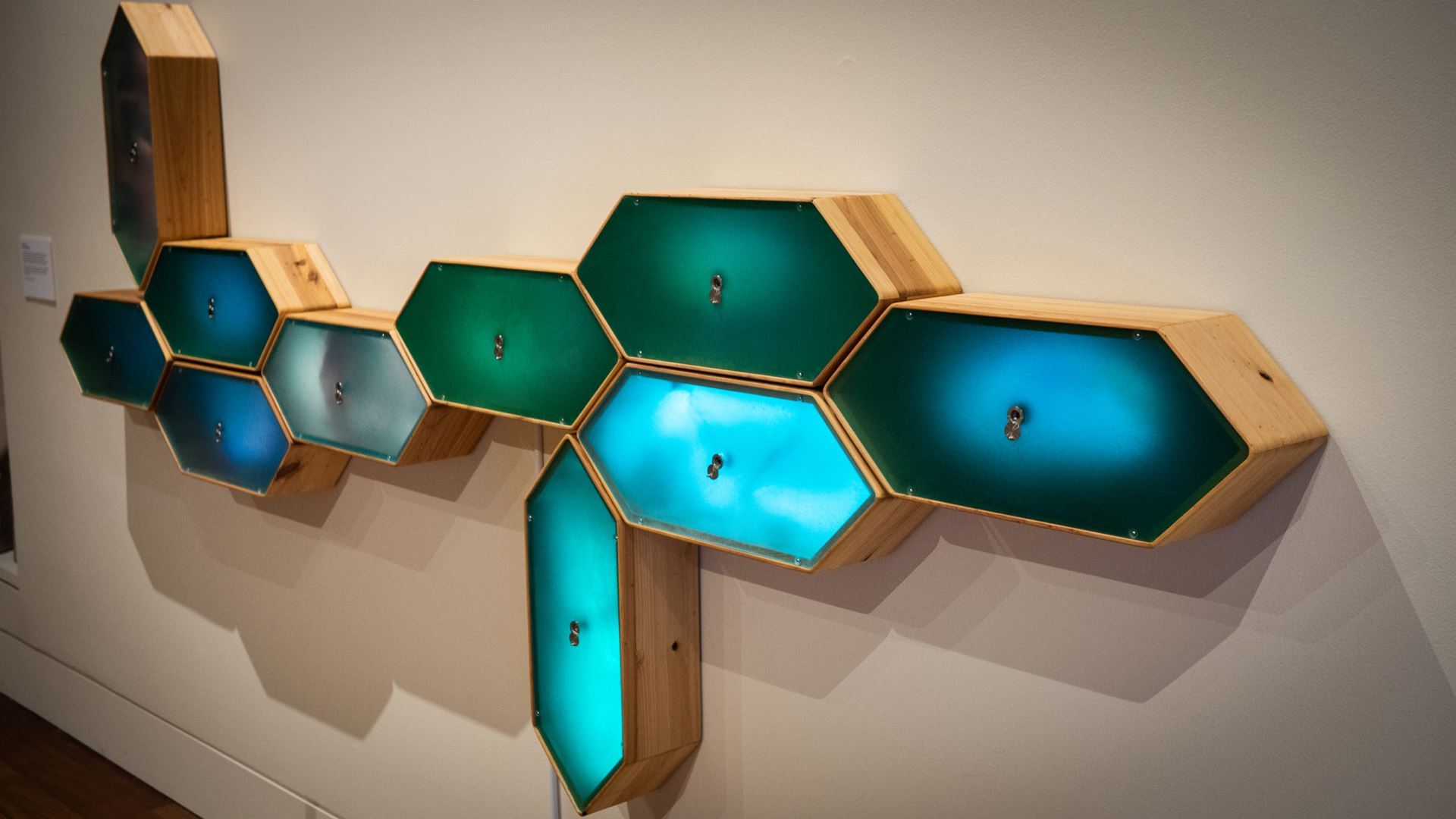

The Algae Society

The Algae Society

Wall Cells, installation view, 2022.

Photo : Bradley Pierce, UNCW, courtesy of Cameron Art Museum

Besides the fact that Algae provides between 50-80% of the oxygen we breathe on the planet, why are Algae important to the art-viewing and general audience?

Jennifer Parker: They are just so beautiful and magical but often overlooked - bringing algae into traditional art spaces opens new pathways for thinking about living systems around us as part of our cultural fabric and common heritage.

Gene Felice: The Algae Society attempts to tell stories about algae through art & science collaborative experiences that make the normally invisible aspects of life on our planet a bit more visible for humans to witness. If we can begin by alluring the public with the aesthetic and functional beauty of algae, the hope is that they will make more informed choices that ultimately impact the health of our water and the life on this planet that depends upon it.

Why are algae important to our oceans and planet?

Jennifer Parker: They are a super special and diverse aquatic organism. They are critical to life on the planet. They lack roots, stems, and leaves so they are very different from other organisms that photosynthesize? - they occur in a huge variety of shapes and sizes and are found in a range of aquatic habitats both freshwater and saltwater. They also are very efficient at using carbon dioxide keeping the atmospheric levels stable.

Dr. Jose Carlos Espinel: I think the impact of algae in our life is much bigger than we tend to think, they do not only produce the oxygen that we breathe but are very important organisms for the different ecosystems where they are present. The exhibition itself works as a tribute to algae. The term “mother nature” talks about some kind of intangible entity that takes care of life on earth and keeps its circle working, looking after the environment and all the living organisms on earth. The term itself leads us to some kind of mystic creature or being, bigger than our self and above our own comprehension. We could be talking about some kind of goddess and in this sense I believe algae could perfectly be acting as some sort of divine being.

Gene Felice: Algae filters much of the air that we breathe turning CO2 into O2, but they’re also the base of our planet’s aquatic food web. Micro algae serve as the photosynthesizing foundation of food for zooplankton, then fish, marine / fresh water mammals and onward. For example, phytoplankton serve as the food source for zooplankton known as copepods which serve as the food source for krill which serves as the food source for one of the largest mammals on the planet, blue whales. Quickly we can see and feel the impact that algae have on all of the organisms on our planet, particularly ones that humans have great affinity for.

Many of the works in the exhibition seem to have been produced with the environment in mind, i.e., not using toxic petroleum-based varnishes, etc. Can you tell us more about the guiding principles for the Confluence Exhibition?

Jennifer Parker: We try our best to use sustainable materials with as low an impact on the environment as possible - it's also a challenge of sorts - as we question our choices and seek alternative materials and methods - we always ask ourselves if it is necessary to make something and what is the value of that something is on our communities? How is it contributing to bettering our environment physically now and in the future? What is the impact of our work, how does it contribute to the waste streams, energy systems, and the future health of ecosystems we work in? - we try to have the smallest footprint possible but it's really hard.

David Harris: Many sustainably focused projects concentrate on how they use resources. Algae is often seen as a sustainable resource in increasing amounts of food, bioplastic, and other products. However, as soon as something becomes just a resource, it becomes open to exploitation. In the Algae Society, we are interested in reconsidering this dynamic so that we consider algae as a partner in our efforts to preserve a livable world. It means considering the short- and long-term needs of algae as well as humans, so that entire ecosystems can thrive. This post-human perspective is a challenge because we don’t even have good language to discuss it let alone yet understand what algal equivalents of rights, ethics, justice, or any other similar human concepts might be applicable.

Gene Felice: When creating a project that seeks harmony within our aquatic ecosystems, it feels counterproductive and hypocritical if the project is made from materials and processes that ultimately pollute those environments. While it can be difficult and expensive to have a zero carbon footprint or to use absolutely all local / biodegradable materials, we do our best to seek out a variety of materials, processes and technologies with biodegradability and ecological impact in mind. For confluence this included 3D Printing material made from corn and wood, seaweed dipped in a mix of beeswax, pine resin and Jojoba oil, sculptural forms made from local cypress wood and CNC’d plywood made with soy based adhesives and finished with Shellac. Instead of plastic window panels we cast our own forms from pine resin and tinted them with Spirulina powder and other mineral based pigments.

What do you feel worked best in this exhibition, and were there any surprises as you installed the works?

Jennifer Parker: That's hard to say - so many of the works are informed by each other - picking just one out would limit its value - the work in the show is valued as a collection dependent on one another to tell a rich and vibrant algal story. Just like our collaborative efforts as a collective of humans, we influence one another through shared experience and conversation -we are always looking to expand and push our ideas to be more relevant and interesting - the work in the exhibition is an extension of our collective conversations with each other, conversations that now include the museum visitors in direct conversation with the work.

Gene Felice: One of the most collaborative pieces from the show is Visions of Algae. The concept for this project bounced between three of us (myself, Jennifer & Juniper) as well as feedback and ideas from all of the Algae Society as it progressed. It started as a ceiling installation but then shifted as we moved into the high ceiling Studio 1 space at the Cameron Art museum. It then became a floor based piece made modularly with different components being created on both the east and west coast of the U.S. Juniper curated the archive of images from all of the Algae Society and beyond and with Jennifer printed them on Japanese rice paper and then dipped them in an encaustic process. I prototyped and 3D printed the lens ring forms that hold the images as well as the CNC milled bases with aluminum rods and fixtures. This combination of sensibilities, skill sets and conceptual frameworks across the group, resulted in a collaborative installation that can adapt to a variety of spaces and configurations based on site specific needs. A lovely surprise was when we installed Visions of Algae into the Cameron Art Museum and realized the morning light through the large corner window illuminates the encaustic dipped images, giving them a warm, translucent glowing quality. At night they also served as dynamic projection surfaces, back lit from a projector used for the Bioluminescent Thursday event series.

Many museums would be reluctant to have living algae or bio artworks within a museum. Was this controversial for the Cameron Arts Museum to accept these elements as part of the Confluence Exhibition?

Jennifer Parker: The Cameron Art Museum is a fantastic place. The director was really open and responsive to all of our ideas. With all the work we do there is a certain level of trust required by the venues as the work is definitely not your typical art exhibition. We want people to pick up work and interact with it, to come back and see what has evolved and changed since their last visit. The work for us is very alive in this way - literally and figuratively

Gene Felice: The Cameron Art Museum and its curatorial staff are both innovative and open minded when it comes to new modes of experiencing art. From experiential groups like Team Lab to our unique blend of eco / bio art, they welcomed us with open arms. Their mission includes major site specific themes such as history and environment and the Algae Society became a perfect fit for the CAM to explore its connections with our local / global water issues, within our particular focus on algae. The museum itself is a stunning environment to create within and the Studio 1 space fits our work in ways that we didn’t fully realize until we were installing. The staff at the Cameron worked with us to create a mix of light and dark spaces as well as a window installation space that can transform at night into a double sided video projection mapped wall of light. Their flexibility allowed us to evolve the show to the space throughout its run, adding new pieces and shifting and adapting experimental work as it evolved through its life cycle. The retention pond on the grounds of the Cameron extended the work beyond the gallery to include our long term, Floating Island Ecosystem bioremediation project.

Do you feel the viewing and interacting audience was able to find a new love of Algae in its myriad of forms?

Jennifer Parker: I hope so! It was our intention to show really diverse works in a variety of media types to spark interest and curiosity with a broad audience inclusive of all ages and backgrounds.

Gene Felice: Our intention is to allure through multi-sensory experiences that foster compelling questions in the minds of our audience. What makes such complex forms? How is it possible that algae produces so much for us (air, food, etc.)? How do our choices affect this multifaceted range of organisms? By cultivating these questions through a multitude of approaches and materials, we hope to reach across multi-generational and political / social divides. One of the most inspiring parts of working in the Cameron Art Museum is that each day the museum welcomes school trips from elementary through middle school as well as families with middle aged parents and babies and older generations of empty nesters and retirees. Each of these groups brings a different set of experiences and questions in relation to our work and the connections between human beings and algae. Some of these questions overlap and others inform each other in new and unexpected ways, shaping the way we evolve our art and science focused work in the future.

How do you imagine the Algae Society could recreate this Confluence Exhibition at other venues?

Jennifer Parker: Working with local residents, creatives in the arts and sciences is one way that we connect and co-create in each of the venues we have exhibited. This includes different types of regional and local algae at the micro and macro levels.

Dr. Jose Carlos Espinal: In this case, the Confluence show had a sister exhibition in Madrid, “Confluir” at the Faculty of Fine Arts at Universidad Complutense, where graduate students developed works related to algae and aquatic environments and the impact of human activity on those. Works developed there were mainly focused on a local level, but keeping a global mindset.

David Harris: Algae Society exhibitions so far have exhibited an ebb and flow of works, with a view to engaging with the needs and interests of communities local to the exhibitions. As we engage different communities around the world, the specific works shown with unique local collaborators help present different emphases but within the broader agenda of the society. For example, we have in mind a future exhibition in Australia that would include a strong connection to and critical involvement of local indigenous peoples and knowledge systems, while also connecting with a robust local institutional research effort.

Gene Felice: The Algae Society is a global collaborative that seeks new questions and art making challenges in each community that it connects with. Confluence was designed to break down into a series of modular parts that can be easily shipped and adapted to new spaces in the future with as low of a carbon footprint as possible. Some projects can be sent digitally and fabricated on site with the tools at hand. Projects like Wall Cells are curatable micro-spaces that can speak and connect to site specific conditions and local ecosystems. Visions of Algae breaks down into a series of flat shipping containers, to reduce space and shipping costs.

Are there other contemporary art science/movements or artists you admire and look to as models for what could be?

Jennifer Parker: That’s a great question. I’m interested in restorative design as a creative practice for imagining new futures of materials using natural resources that protect and restore biodiversity of ecosystems.

Gene Felice: Each Algae Society has their own influences, but here is a short list of art & science groups / artists / architects / collaboratives that have inspired me during the production of Confluence:

https://www.ecologicstudio.com/

http://bestiaryanthropocene.com/

https://feralatlas.org/

https://collinsandgoto.com

https://www.julialohmann.co.uk/

https://www.laurasplan.com/

What is next for the Algae Society?

Jennifer Parker: We are in conversation with venues in different parts of the world to exhibit and develop new works and exhibitions in the future - we welcome interested parties reach out and connect

Gene Felice: We’re ready to develop new, site specific work as Jennifer mentioned and we’re also ready to adapt the Confluence show to its next location in a museum, gallery, science center or non-traditional space. More importantly, we seek to connect to aquatic ecosystems in need of a voice or a new connection for asking questions that foster balance and understanding between human and nonhuman needs.

Ken Rinaldo

Algae Sign, 2022.

Photo : Bradley Pierce, UNCW, courtesy of Cameron Art Museum