“Tree Talk,” 2018, Ponderosa Pine Tree sonification

Anne Yoncha Interview by

Olivia Ann Carye Hallstein

Anne Yoncha speaks with the trees. Through biodata depiction using galvanometer sensors and speakers, Yoncha presents the experience of plants, peat and prairie grasses in an eye opening, often minimal, aesthetic. By presenting biodata in its raw form, she allows the environment to be amplified so that all of us can hear the stories of the Pines. Based in Oklahoma, USA, the artist works closely with scientists and composers to create multisensorial interactions between humanity and an otherwise invisible world.

Art allows us to see, feel, hear environmental processes that are otherwise invisible to us, operating at a different scale or a different timeframe.

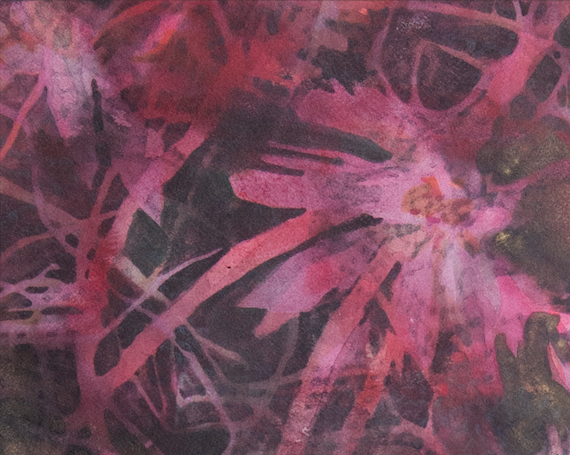

“Succession: A Visual Score” 2019, sonified biodata composed with cello recording

Much of your work encompasses and visualizes existing issues and studies related to environmental sciences. What can art as a platform do that research alone cannot?

Art allows us to see, feel, hear environmental processes that are otherwise invisible to us, operating at a different scale or a different timeframe. We suddenly have access to a more direct understanding of an experience beyond our typical human one. Maybe we are able for a moment to experience some of the processes and pressures on a lifeform which is not our own. Maybe it leads us to draw parallels to our own experience (for example, our human death from embolism would be physiologically similar to a plant’s death from drought). Maybe it leads us to act, or maybe just to be curious. I think this open, questioning, expanded experience is crucial as we can increasingly access more information, because information doesn’t always lead to understanding. When understanding of our ecological problems is limited, artists have historically been successful in uncovering background narratives, shaping how scientifically declared emergencies are perceived and acted upon.

Artists have historically been successful in uncovering background narratives, shaping how scientifically declared emergencies are perceived and acted upon.

“Second Wind” 2019, Depicting pine tree wind velocity

In order to create this awareness, you often use technologies to transcribe environmental phenomena like in Tree Talk or Succession: A Visual Score or Second Wind. These pieces are embodiments of usually unheard environmental interaction. How do you collaborate or use tools as a bridge for understanding? What is this process like?

I first became interested in this idea of transcription in 2018 when I was playing with a galvanometer sensor and some Ponderosa pine seedlings. We had a room of artists and plant physiologists, using a synthesizer to make the plants sound, at one moment, like an uplifting orchestra, at the next, a quieter, mournful organ. Any decision we made about how to sonify the data was entangled with our subjective choices. In “Succession”, I wanted to explore this idea of reading and interpreting data about two plant groups in conflict. The drawing was my own reading of the place, the data overlay was the sensor reading. Then, I handed the project off to my collaborators, and they read the piece too. Now, as the red cursor moves across the video, the viewer is the last reader. In “Second Wind”, I was interested in performing data –wind data, in the gallery, in real time. We are so focused on collecting data, gathering it, analyzing it later. So, giving it a moment on “stage” and letting it go seemed like a bit of a radical act. Would we pay more attention to it, knowing we could only keep it for a moment?

Would we pay more attention to it, knowing we could only keep it for a moment?

“RE:Peat, Layers of Peat in Northern Finland, a Look and Listen” 2019

By performing data, you are letting the elements speak for themselves rather than through interpretation. As a result, much of your work is highly educational and revealing about the world otherwise unseen. Do you have a mission for this work? What has been your inspiration?

Media theorist Boris Groys wrote about the difference between the digital image file, which is always consistent but impossible to experience, versus the digital image, which we experience as a unique manifestation each time we open the file. I am interested in the distinction between the data itself and our experience of it. Philosopher Albert Borgmann’s “device paradigm” critiques how we consume technological devices and their outputs yet separate ourselves from their mechanics. The digital world has brought us so much connection at the price of so much detachment. I want to extend this thinking into the bio-art realm, building scientific and aesthetic understanding of how we consume ecological systems, while conceptually and emotionally separating ourselves from the damage we do to them. I also see my work as a way for me – and hopefully if all goes well, viewers also – to pay attention. Many of my projects are assignments I give myself to satisfy curiosity about how digital and analog processes work.

…the bio-art realm, building scientific and aesthetic understanding of how we consume ecological systems, while conceptually and emotionally separating ourselves from the damage we do to them.

Lab (2018), Pine Seedling Regrowth, Study and Sonification

So, you are acting not just as a translator between environments, but also between digital and material. Many of the materials you employ are machine based or highly tactile like cloth or painted paper. What appeals to you about this contrast between rationality and tactility?

Tactility makes us feel something! But in all seriousness, I first heard the term “data materialization” from fellow artist Courtney Starrett and it has stuck with me ever since. We can do more than just visualize data. The materials and processes we use can also add meaning and impact. This is fun for me, too, because it means I can learn new processes based on each place and ecosystem I’m making work about. I love this contrast between rationality and tactility, between subjectivity and objectivity, because it gets blurred once you really break down our methods of collecting and interpreting information. I try to make work which points out that slipperiness.

The materials and processes we use can also add meaning and impact.

Thank you, Anne, for a wonderful interview! I look forward to hearing where your work takes you next. Oliva