Still from Food for Thought Exhibition Video

Still from Food for Thought Exhibition Video

The Big Picture, Up Close:

An Interview with Robert Dash

Olivia Ann Carye Hallstein

Robert Dash is a widely recognized and accomplished photographer and a great admirer of the natural world. As a naturalist, artist and educator, Robert uses micro-photography to provide a new dimension of depth to our common understanding of the world around us. Through these incredible photographs, Robert emphasizes the complexity and importance of nature and stands as a reminder that there is so much to discover. Providing an important intersection between scientific inquiry and artistic expression, Robert’s work epitomizes a necessary relationship between study and discovery. In this interview, Robert takes us on a journey through terrains the size of a pinhead and gives incredible insight into reflection and intimacy with the natural world.

Hummingbird Feather Detail from Micro Climate Change

Hummingbird Feather Detail from Micro Climate Change

Robert, your work stands at the intersection of art and science. By looking at objects in your surroundings very closely, you present mesmerizing photographs. What is the greatest wonder that you have found in this micro world? What do artists have to learn from looking at things extremely closely? Many artists were historically also scientists, how do the two disciplines interact?

Science (fact) inspires art (metaphor) which stimulates imagination, curiosity, inquiry (and new facts…) Remarkable textures and patterns in nature are beautiful in their own right. They can also inspire deep questions, observations, perhaps a lifetime career or Nobel prize.

Look at the underside of this hop leaf and olive leaf. I was stunned when I first saw these. These structures are a fraction of a pinhead wide.

Hop leaf detail

Olive leaf detail (underside, with trichomes)

I love to hike when I come upon views and perspectives that I’ve never seen before. Most of the time, I’m on a trail that thousands of people have already visited. Macro photography and SEM imaging are like micro-hikes, going to micro landscapes which few (if any) have seen before. Some of what I find is mind-blowing, design-wise, and overwhelms my imagination. On the other hand, looking closely represents an aesthetic and personal choice to settle down, observe, and patiently contemplate a subject, which is counter to so much of modern frenetic lifestyles. My first book, On an Acre Shy of Eternity, was a three-year quest to look at all the layers of beauty I could find on the three-quarters of an acre where I live. It’s what started my work with a scanning electron microscope. Slowing down for that period inspired contemplation and poetry.

Both science and art deal in awe, wonder, surprise, and creativity, but for the sake of conjecture and over-generalizing: art leans toward the infinite, imagined, nebulous, while science leans toward the finite, provable, precise. Maybe art makes us feel, first, while science makes us think, first.

In your TEDx talk, you discuss the topic of “eco-intercourse” that happens when breathing in air in a forest surrounded by leaves that create oxygen. Can you expand on this shift in perspective and the consciousness that it creates?

I’ll answer with my poem:

Primal Exchange

There’s a whole ocean in the sky:

drops sucked from lakes where we swim,

clouds at dusk that leave us breathless,

salty residues of our grief and toil.

All of it

filters through pinpoint cells on leaves and plants

over and over each year.

They barter pure air for our exhalations

in the primal exchange.

Every stomata

on all plants of the world could match in number

stars in the sky

and like stars, they need songs and sonnets of their own.

Bring a loved one out beneath the trees

send your breaths up to constellations and galaxies of stomata

and receive their breaths in reply.

What could be more intimate than the truth

that our bodies are made of each others’ atoms

And those of the world?

Robert Dash, On An Acre Shy Of Eternity, ©2017

Poplar Stomata

Poplar Stomata

Your metaphors are so intimate and reflect this feeling of awe when encountered with wild landscapes. How has this eco-intercourse driven your most recent work, Food For Thought, where you present extreme close up images of climate resistant crops and of compost?

Three years ago, my images were all about climate threats to staple foods such as corn, beans, wheat. Drought, floods, disease, nutrient depletion–there are many grim stories. The more I studied, the more I learned about carbon farming and regenerative agriculture, and I became excited about how these practices could help reverse climate change. Since scanning electron microscope work is so labor intensive, I only took food samples to the lab which had either a connection to these climate perils or promises. I looked at hundreds of samples, and then chose the ones which made my jaw drop when I first saw them.

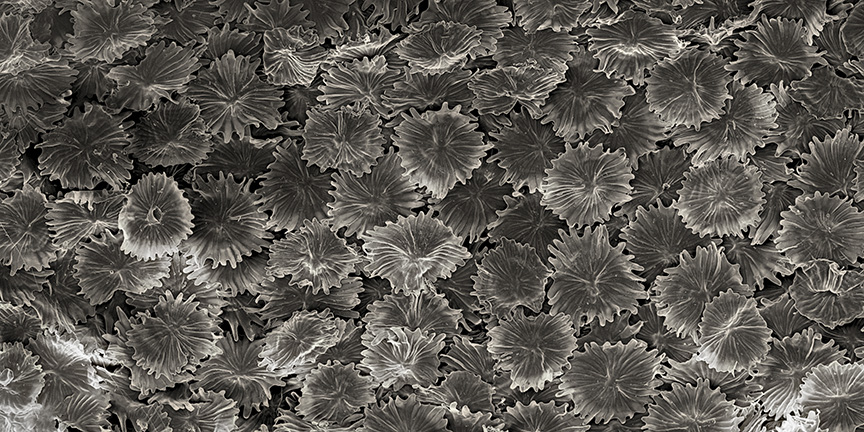

More than an individual plant that creates climate resilience (and there are many, including agave in deserts, kelp in coastal areas, fava beans and clover cover crops on croplands), by far the most impactful practices are the rebuilding of soil, by storing more organic matter (carbon) there. The film “Kiss the Ground” explores this. My biochar image helped me understand why adding compost and biochar to the soil is so significant. Biochar is sometimes called a “microbial hotel” because of all of the hiding places it provides for microbial organisms and decomposers so important to rich, organic soil. The crystalline structure displayed in this image floored me, especially when you consider that the piece of biochar depicted is roughly the width of a pinhead.

…macro and micro, color and monochrome, fact and metaphor, surreal and hyper-real, serious and whimsical, flat and dimensional. Just like life, which is so layered and complex.

Biochar

Really beautiful and insightful! How do you decide to integrate your microscopic images into artworks? What methods do you use?

Master photo composite artist Jerry Uehlsman uses the term “assets” when describing the separate elements which comprise his work. These assets come together on a “canvas” and present a shape, color, texture, pattern, or metaphor. The trick is to discover what conversation these elements can have to make a unified image. Does the image suggest a story or world? Does it invite deeper study? Does it “work”, without feeling forced or contrived? Some of these images took years to resolve. For example, I was stuck with the potato image for the longest time, until I saw the starch granules, magnification 1000x, as tiny potatoes. By pairing macro potatoes with “granular potatoes”, the image finally clicked.

Potato Starch

I have noticed that many of your works for Food For Thought take place on a black background, with monochrome microscopic imagery and highly defined and saturated imagery. How did you decide on this aesthetic?

The simple answer is, I love how it looks. A black background creates a dramatic contrast to the macro and micrograph images, and that drama mirrors the impact of awe and wonder I feel in nature. Then there are the pairings of macro and micro, color and monochrome, fact and metaphor, surreal and hyper-real, serious and whimsical, flat and dimensional. Just like life, which is so layered and complex.

I’m not a digital native. My native comfort zone as a child was hanging out with salamanders, frogs, snakes, insects, and tadpoles.

You speak and write compellingly about the importance of investing in nature. What do people need to know about the natural world? How do you think growing dependence on digital technology is helping and hurting this relationship?

Having been born deep inside the last century, I’m not a digital native. My native comfort zone as a child was hanging out with salamanders, frogs, snakes, insects, and tadpoles. This cemented my fascination with tiny life. Humans have an ancient, intimate relationship with nature that is spiritually vital. A huge range of modern anxieties–alienation, depression, isolation, rage–are connected to syndromes like Nature Deficit Disorder (NDD), where we’ve lost that contact.

I spend far more time with screens than I ever thought possible. Much of it is an attempt to translate, through art, my lifelong love for nature. Our attention spans have been fractured by the juicing of brain chemicals that come from digital surfing, and this damages our ability to think deeply, and to create. I worry that this is numbing us to the ancient joys of belonging to wild things, and to caring enough about them to protect them. Digital tools can help promote conservation–think drones that disperse seeds over wide deforested areas, or that document poaching in remote lands. Beneath it all is a question: how does this technology serve the cause of balance, restoration, health?

Requiem for the Pollinators

Lastly, what are you working on now?

The Food for Thought work is issue-based, looking at climate change impacts on food. All of my text for this (upcoming) book is about documenting climate/food perils and promises. It’s a very different focus from my first book. Each image reveals layers of stories, but this is a narrative rather than a poetic journey.